Affiliate links on Android Authority may earn us a commission. Learn more.

What's the safest way to lock your smartphone?

Published onSeptember 5, 2017

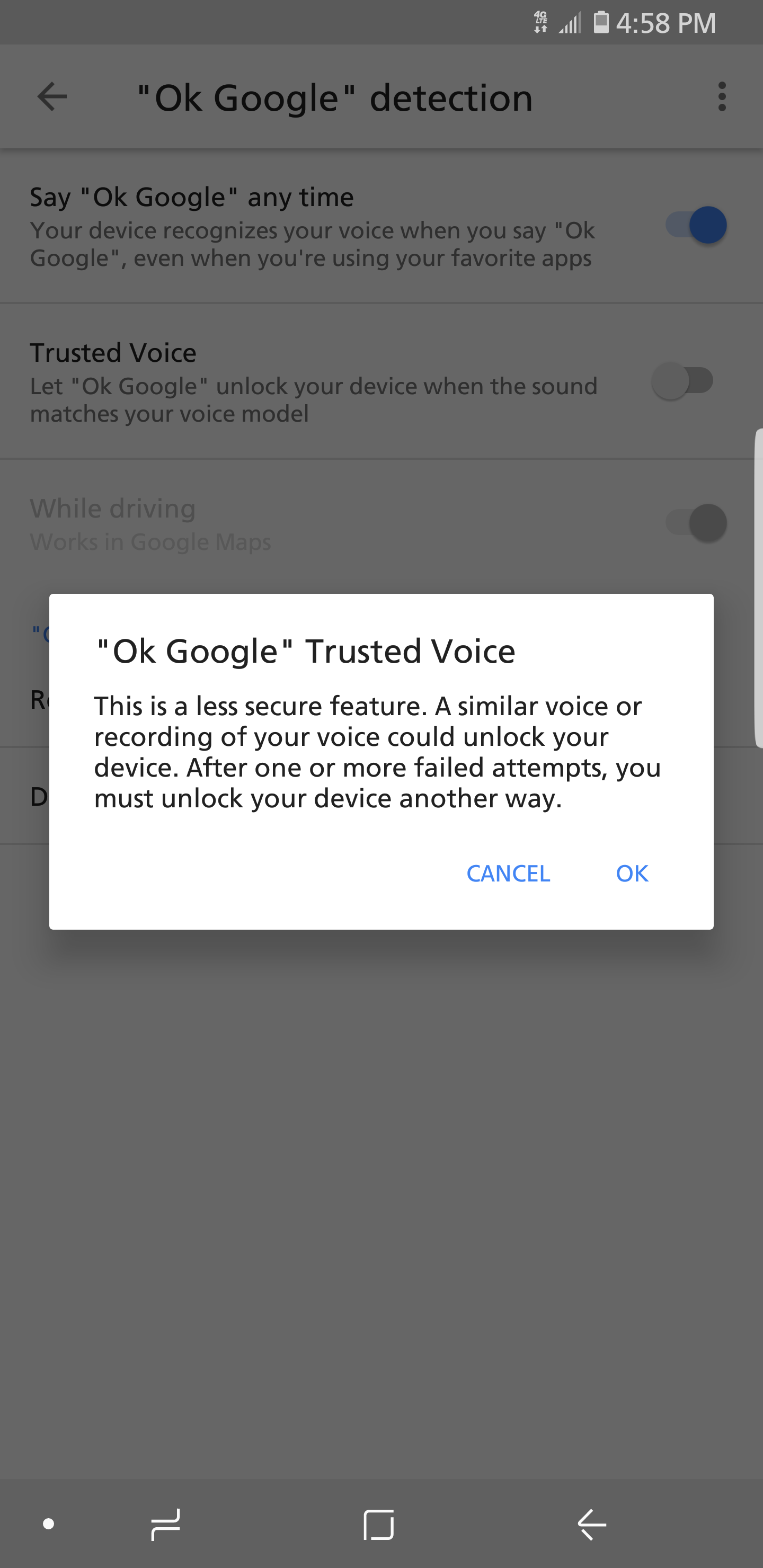

Whether or not you care about the minutiae of mobile security, it’s likely that you care about your privacy, and that leads us into the topic of this article: biometric vs. non-biometric security. In particular, what is the best method of locking your mobile device?

Biometric and non-biometric: What’s the difference?

By definition, the term biometric refers to biological data, which can be something as accessible as a fingerprint or as intense as genetic data. However, for our present purposes, you should assume that I’m referring to biometric authentication, which is the use of a person’s biological characteristics to verify his or her identity. But the simplest and most straightforward definition is that when you’re using a biometric form of mobile security, you are your password.

For a smartphone, it works like this: when you setup biometric security, you begin by first providing a biological sample that is digitized and stored as read-only information on the device. As you might have guessed, it’s stored as read-only so it prevents the information from being modified or compromised, which is what makes it reliable despite the fact that it exists as raw data somewhere on an extremely fallible device. And when you need to gain access to the device, you have to provide another biological sample that is checked against the sample that was stored initially. If the samples match, you’ve proven your identity and gain access, but if your sample doesn’t match what’s stored, you’ve been unable to verify your identity and, therefore, get denied.

Non-biometric authentication equates to the use of a password, PIN number, or pattern as a means of verifying your identity. Our digital lives have been ruled by passwords until only very recently. We’ve grown accustomed to using them to secure our Facebook and Twitter accounts, our Gmails and Yahoos, our Amazon accounts and even our online banking. On paper at least, these non-biometric forms of authentication are considered much less secure, but are their biometric counterparts actually infallible?

To be clear, the reason that passwords are so insecure is because there are a finite number of possible alphanumeric combinations that can be used for any given password, so a hacker with the time and tenacity could, in theory, figure out your password through a process of elimination. Or else, a potential attacker could watch you input your password or pattern and, after gaining access to your device, attempt to follow along with your movements to satisfy your device’s authentication requirement. Granted, there are ways to mitigate this somewhat, including by putting a limit on the number of times in which an incorrect password can be entered, but this type of precaution is far from absolute. For this reason, fingerprint sensors are all the rage right now and are becoming a standard feature even on mid- to low-range mobile devices.

“The password you’ve entered is incorrect.”

I’m sure the question has occurred to you at some point over the course of your smartphone tenure: What’s so wrong with using a password?

As I mentioned above, there are a finite number of different passwords that any of us can use. Of course, the likelihood that a stranger would be able to arbitrarily guess your password is extremely small. However, if the perpetrator is someone you know, and if you’ve chosen a password that’s somehow related to you or your life, that person has much better chances of overcoming your device’s security. In fact, the potential to be hacked by a loved one is one of the biggest factors when it comes to choosing the right security method for your device, and that’s a point we’ll come back to in a moment.

But what about the capital letters and special characters I’m required to include in my password? Doesn’t that make my device more secure? Actually, no.

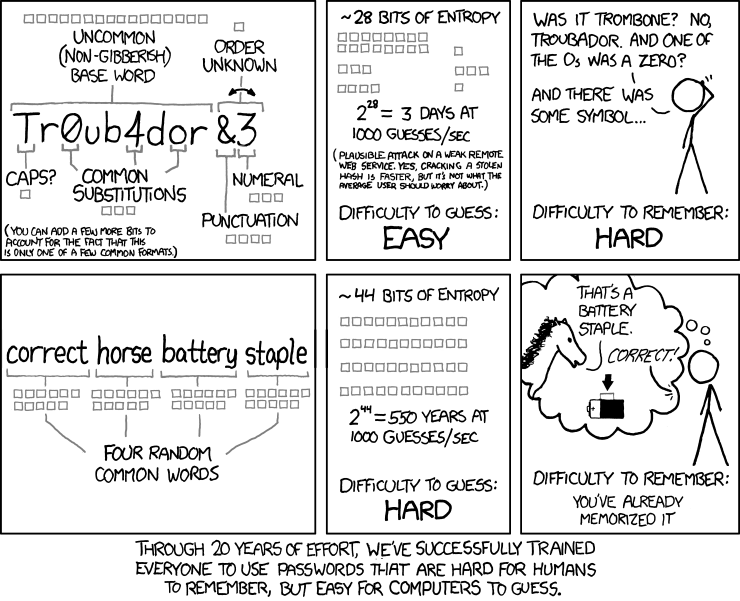

If the man who’s responsible for all those guidelines that are supposed to make our passwords more secure is to be believed, including the capital letters and numbers and special characters doesn’t actually make your password more secure. That guy’s name is Bill Burr, a former manager at the National Institute of Standards in Technology (NIST).

In 2003, Burr created an eight-page guide that would go on to inform the password-creating guidelines by which we’re forced to abide today. But Burr recently came clean and admitted that he had a very poor understanding of how passwords actually worked at the time, and he’s very sorry that his misguided treatise is the reason we must make these unnecessarily complicated passwords that don’t make our devices or accounts anymore secure.

We now know that using a string of simple and unrelated words is actually more secure than using a shorter password in which there is a mix of upper- and lowercase letters, numbers, and special characters. There’s a well-known comic strip that explains it best, illustrating how a computer would take 550 years (at 1,000 guesses per minute) to figure out a password consisting of four simple words like “correcthorsebatterystaple” while something like “Tr0ub4or&3” would take just three days at the same rate.

It’s important to realize, though, that adopting the best practices for password-making doesn’t change the fact that we’re becoming more vulnerable to hacking than ever. We no longer live in a world where your smartphone and your PC are the only access points to your digital life. Smartwatches and other wearables, tablet computers, internet-connected hubs, smart TVs, and a plethora of other web-connected technologies are just a handful of the growing number of devices onto which we’re putting our private accounts and information. And just as your smartphone’s security isn’t infallible, each new connected device has its own security vulnerabilities, too.

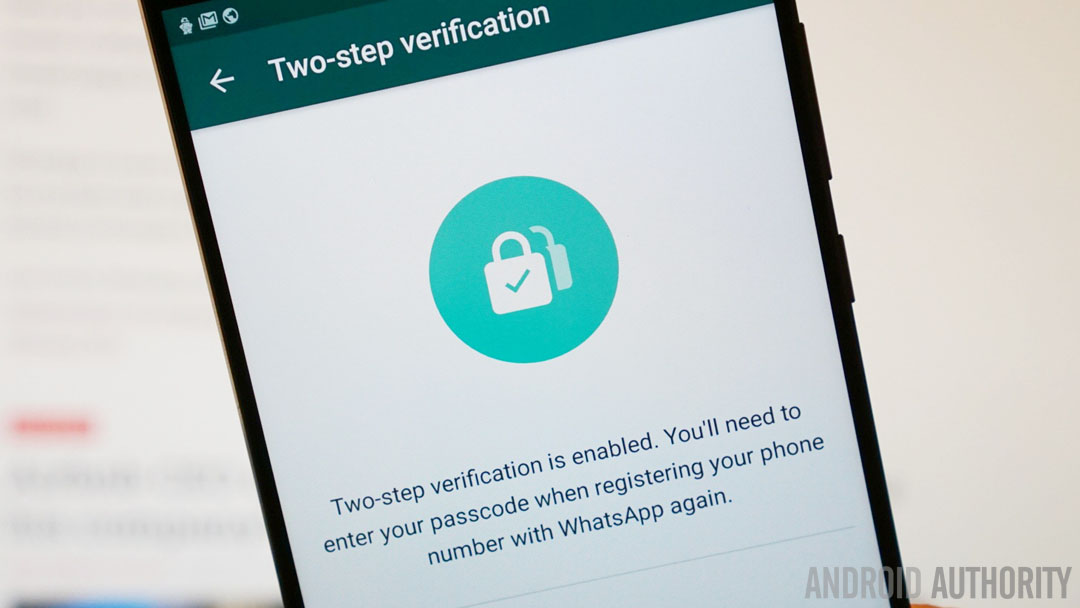

If there’s a saving grace for alphanumeric passwords, it’s the advent of two-factor authentication. Rather than immediately granting entry, two-factor authentication will trigger a one-time temporary code to be sent to you, to be used in conjunction with your regular password.

If there’s a saving grace for alphanumeric passwords, it’s the advent of two-factor authentication. Basically, rather than immediately granting entry with the input of your password, two-factor authentication means the input of your password will trigger a one-time temporary code to be sent to you — typically a numeric code sent via a text message or phone call — and you can only gain entry once you’ve input that temporary code in the login window.

Of course, while it’s more secure than using a password alone, two-factor authentication is really only useful for logging into web-based accounts and isn’t viable for locking your smartphone. If we only used two-factor authentication on our mobile devices, your smartphone would basically be unusable anytime you happened to be in a dead zone or on a flight, for instance, since two-factor authentication typically requires some type of data connection so the transmission of the temporary PIN code can be triggered. There are ways around this – like using an app on another device, or something like YubiKey – but they are impractical for every-day consumer use.

Patterns have been a very popular method of smartphone security, too. While passwords require alphanumeric input and, therefore, is a more deliberate or even tedious process, patterns are much faster and easier to do, particularly when you’re using the device one-handed.

To set up a pattern, you’re presented with nine dots arranged in three rows of three; essentially, you start by putting your finger onto your desired dot as a starting point and play a little game of connect-the-dots, drawing connecting lines to other dots to form a pattern. You can draw connecting lines between three dots, five dots, or ten dots, making the pattern as simple or complex as you’d like. Once your pattern is set, anytime you wake the display of your device, you’ll see those nine dots and can begin inputting your pattern to unlock.

In addition to being forgiving to one-handed use, people tend to like using patterns to secure their phones because they can rely on muscle memory to input their patterns and unlock their smartphones almost without looking or giving the process any thought. However, one of the biggest issues with patterns is that others can watch how your finger moves across your device’s display to decipher your pattern. It’s particularly easy since there are only nine points on your device, giving hackers much better chances of figuring out your pattern than if they were trying to detect the letters you were hitting on a keyboard for an alphanumeric password. And almost half of lock screen patterns start in the upper lefthand corner, according to some data.

Between all non-biometric forms of smartphone security, passwords are definitely the most secure, especially if you’re smart about how you make them. But if you want to be as secure as possible, shouldn’t you be using biometric authentication?

You are the password

Until last year’s ill-fated Galaxy Note 7, mainstream consumers mostly had one type of biometric security available to them, which was fingerprint sensors. In fact, the past few years have seen fingerprint sensors emerging even on low-cost devices, including the ZTE Blade Spark (available from AT&T for a single Benjamin) and the iPhone SE, an iOS device that currently dons a rare sub-$200 price tag. Now we’re also seeing iris scanners, and they’re no longer limited to devices like the Samsung Galaxy S8/S8 Plus and the freshly-Unpacked Galaxy Note8. And surely it’s only a matter of time before we’re seeing other types of biometric authentication make their way to our mobile devices in the years to come.

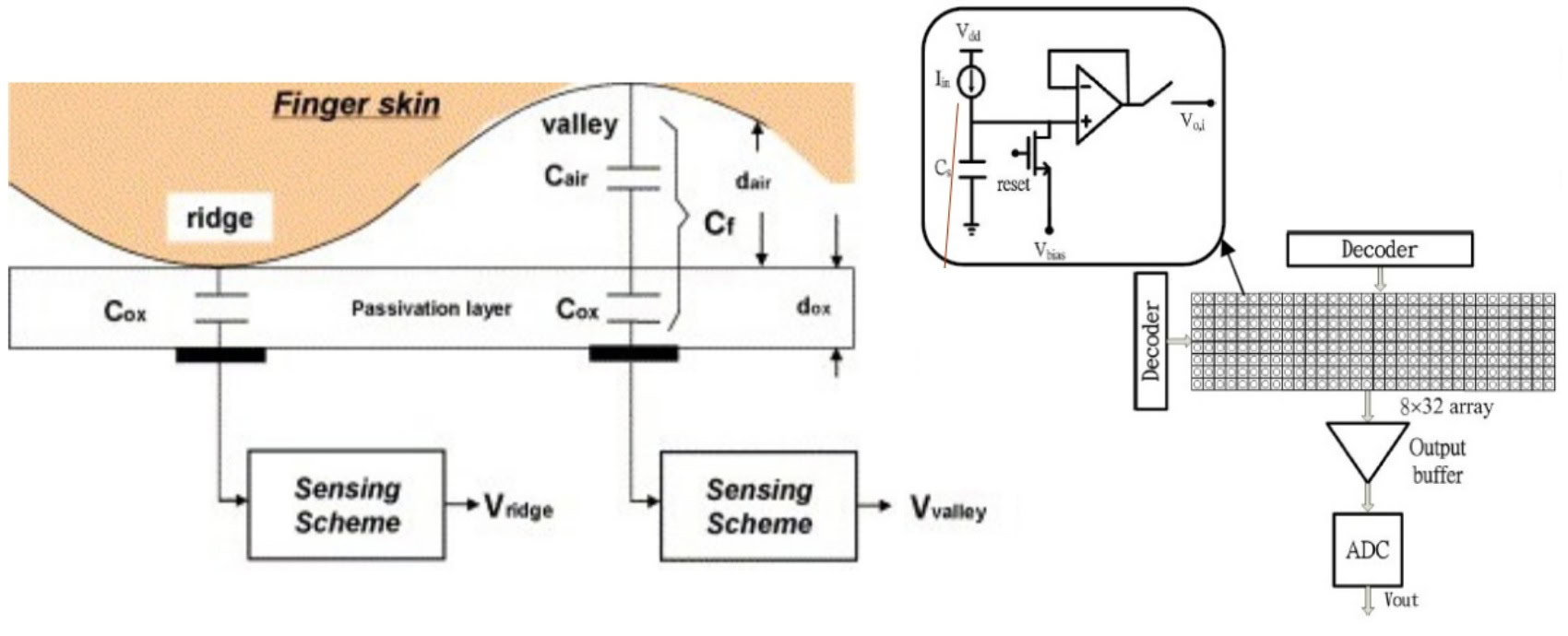

Starting with the fingerprint sensor, there are a few different technologies that could be used, and our own Robert Triggs created a great guide to differentiate between them; however, for our present purposes you should know that virtually all fingerprint sensors on mobile devices are capacitive fingerprint sensors. (On a side note, ultrasonic sensors — which experts agree are even more secure than capacitive — will be necessary for OEMs to finally crack the code and embed the sensor into the phone’s display.)

A capacitive fingerprint sensor consists of lots of tiny and tightly-packed capacitors that are extremely sensitive to changes in electric charge. When you place your finger on the sensor, it creates a virtual image of your fingerprint by inferring the pattern from the different levels of charge between the ridges and valleys of your print. While something like an optical fingerprint scanner can be fooled with a high-resolution photo of your fingerprint, capacitive scanners are more secure because they measure the actual physical structure of your fingerprint. As such, using your fingerprint to secure your device is probably going to be the most secure method available to you. But how secure is it really?

Unfortunately, not even biometric security is completely infallible. In fact, Kyle Lady, Senior R&D Engineer of Duo Security, doesn’t consider biometric security on smartphones to really be any better than non-biometric security methods. According to Kyle, biometric technology on smartphones represents a shift mostly in accessibility and offers “a different set of properties to passwords; not better or worse, but different.”

Moreover, one of the main reasons that we’re seeing biometric authentication for smartphones really take off is because using a fingerprint is easy. “Tied with speed of authentication (biometrics are way faster than a sufficiently secure password), I would say the biggest upside to mobile biometrics is the ease of setup,” Kyle said during an email exchange. Kyle’s company makes Duo Mobile, a popular security app for supplementing your mobile security with multi-factor authentication, and according to Kyle, approximately 84 percent of Duo Mobile users are using fingerprint authentication.

A different set of properties to passwords; not better or worse, but different

Professor David Rogers — CEO of mobile security and consulting firm Copper Horse and lecturer at the University of Oxford — had similar things to say. As a personal challenge, Professor Rogers and his students attempted to fool each of the authentication methods available on modern smartphones; accordingly, they have managed to best every single one, including fingerprint sensors, for no more than the cost of a cup of coffee.

During a conversation I had with Professor Rogers, he explained to me how they managed to trick the fingerprint sensor, which they did with so-called “gummy fingers.” Basically, gummy fingers are fingertip replicas made of rubbery, silicon-like materials that are able to capture sufficient fingerprint detail to fool a capacitive sensor.

Likewise, Professor Rogers explained that these sensors can also be fooled by high-resolution photos of a fingerprint printed in conductive ink, which can mimic the differences in electrical charge between the ridges and valleys of your actual fingerprint. Both the gummy-finger and conductive-ink techniques have been known problems for fingerprint sensors at least since the 1990s.

There’s another issue with fingerprint authentication, and it’s that we aren’t yet certain how secure it actually is. Of course, there are estimates, including Apple’s estimate of a 1-in-50,000 chance of a false match on a smartphone with just one fingerprint registered. If all ten fingerprints are registered (which Kyle Lady doesn’t recommend), the chance of a false match increases to 1-in-5,000.

Meanwhile, Google hasn’t released any estimates regarding the reliability of fingerprint sensors for securing Android devices. Professor Rogers mentioned that, while the base hardware and software is often very solid, there can be some major changes made to the algorithms by OEMs as the Android operating system passes through numerous hands between the implementation of biometric security at Google and the launch of a mobile device with biometric sensors. As Rogers put it simply, the algorithms that facilitate biometric security have to “deal with lots of different humans.”

So is biometric authentication better than using a password? For sake of example, let’s pretend we’re hackers and we want to hack someone’s phone. We know this particular phone requires an eight-character password that can include upper- and lower-case letters, numbers, punctuation, and special characters, and it must have at least one of each. If we do some mathematical gymnastics, there are 3.026 × 1015 possible password combinations. So which is statistically more likely, a false positive from a fingerprint sensor or figuring out the correct password? Even if we have unlimited password attempts and an unlimited amount of time, the two aren’t exactly on a level playing field.

The obvious question is why do we use fingerprint sensors at all if they’re statistically less secure? Well, it’s not actually as black-and-white as statistics might suggest. For one thing, when you place your finger onto a fingerprint sensor, it doesn’t matter if others watch you and see which finger you use because your fingerprint isn’t something they can mimic. Conversely, the fact that people can get your password from you by watching you type it in is a major strike against passwords.

Fingerprint authentication isn’t the only form of biometric security we’ve been seeing on Android devices. Specifically, you might also be wondering about the facial recognition that’s been available since before fingerprint sensors became standard smartphone fare. Facial recognition counts as biometric, right?

Biometric data could include a fingerprint, face, or iris scan, while non-biometric security includes a password, PIN number, or pattern.

For the most part, the facial recognition currently available on Android phones is biometric authentication insofar as your face is the password. While it does meet that technicality, the consensus seems to be that facial recognition isn’t quite in the same league as a fingerprint sensor when it comes to biometric authentication because facial recognition can often be circumvented with a photograph. Check out this video of a user besting the Galaxy S8’s face-recognition feature by “showing” the device a selfie on his Galaxy S7. Clearly, this makes facial recognition quite insecure and, therefore, contradicts the basic premise of biometric security. For facial recognition to be a bonafide biometric, your face must be the one and only way to satisfy the security requirement and gain access.

Iris scanners are another type of biometric authentication that has been emerging on our smartphones. We saw it briefly on last year’s Samsung Galaxy Note 7 as well as this year’s crop of Galaxy devices. Other OEMs are working on incorporating the technology, too, including Nokia, vivo, Alcatel, UMI, and ZTE. Meanwhile, iris scanners are increasingly cited as the best security for your mobile device, even better than a fingerprint. But how, exactly, do they work? And why are they better than a fingerprint?

Much like a fingerprint, your iris — between the pupil and surrounding white, the iris is comprised of lines radiating outward to make up the colored part of your eye — is totally unique to you, making it a prime point of comparison for biometric authentication. But rather than needing a super-high-resolution camera and optimal lighting conditions to capture the unique patterns of your irises, directing an infrared light at your irises makes those patterns clearer, more vivid, and easier to detect in all lighting conditions. In turn, your smartphone converts the patterns of your irises into code, against which it can compare future readings to verify your identity.

Many consumers might be under the impression that the up-and-coming iris scanner is going to be the most fool-proof way to secure a device. However, whether or not they’re more difficult to fool than a fingerprint sensor, we’re learned that not even iris scanners are infallible. Less than a month after the launch of the Galaxy S8 and S8 Plus, The Guardian published a feature about a group of German hackers who tricked Samsung’s iris-scanning technology. The hackers created an artificial eye using a printer and contact lens as well as high-resolution photographs of the registered user’s iris. Notably, it was a night-vision photograph since the infrared light brought out more of the details in the iris, just like the S8/S8 Plus use infrared to capture a user’s iris. Clearly, we can’t totally count on the much-lauded iris-scanning security that’s only just making its way to market.

It’s not surprising that biometric mobile security is so tricky. As Professor David Rogers says, “If you think about it, you’re essentially walking around broadcasting your password to the entire world,” leaving your fingerprints on every doorknob, coffee mug, piece of paper, or computer keyboard you touch, and providing your irises in every selfie you post to social media. So if you’re planning on utilizing the iris scanner on the Note 8 or if you currently use your device’s fingerprint sensor, it’s worth taking a moment to think about how easy you’re making it for someone to steal your biometric data.

Are we thinking about this the wrong way?

Speaking of stealing biometric data, now that we’ve compared the key methods of securing our smartphones, it may be a good idea to think about the types of attacks to which we’re most vulnerable. According to Professor Rogers, there are three main types of attacks that could make you second-guess biometric authentication, particularly when it comes to using your fingerprint.

The first type is what Rogers calls “the sleeping-parent attack.” Basically, this is when children place their parents’ fingers on the fingerprint sensors of their devices to unlock them while they sleep. As long as the parent doesn’t wake during this nighttime espionage, the child can use the parent’s print to gain access to the phone and make unauthorized purchases. However, even though Rogers refers to this as the sleeping-parent attack, virtually anyone who lives with other persons is vulnerable to this type of attack, as this is likely the same way that a spouse or significant other would plant spyware on your device. In any case, if you’re not the lightest sleeper, an alphanumeric password could be a better option.

While you can plead the Fifth Amendment to keep from having to divulge your password, biometric security doesn’t currently apply

Another type of attack is called “forced authentication.” This is when someone forces you to use your fingerprint or iris to authenticate and unlock your device. Rogers points out this type of attack may be seen in street theft — and there have already been instances of this reported in the news — or if the police were to force you to unlock your device. After all, while you can plead the Fifth Amendment to keep from having to divulge your password, biometric security doesn’t currently apply. (There’s actually a lot of legal gray area surrounding biometric mobile security.)

Last but certainly not least, there’s the issue of stolen biometric data. This isn’t super common and it’s typically high-profile individuals — i.e., celebrities, politicians, Fortune 500 CEOs, etc. — who are victims of this type of attack. In fact, there have been instances of celebrities having their fingerprints replicated and Google is practically overflowing with high-resolution close-ups of celebrities’ faces. The issue is that, as mentioned above, we’re constantly leaving our biometric data all over the place. Plus, just as our smartphone technology evolves and improves, those who can replicate that data are likewise developing easier, faster, and more reliable ways of doing it. So if someone with the know-how wants to replicate someone’s print or fake an iris scan, it’s well within the realm of possibility. And particularly when it comes to your fingerprint, once that data has been stolen it’s game over in terms of security.

And the winner is…

It’s difficult to say definitively which is the best method for securing your smartphone because, as you’ve now seen, all methods of biometric and non-biometric authentication have weaknesses. On paper, biometric authentication should offer the most security, but there are inherent problems even with iris scanners.

One possible solution that could alleviate the shortcomings of both biometric and non-biometric authentication would be to allow users to activate multiple security measures at once. For instance, on the latest-generation Galaxy devices, requiring both fingerprint and iris scans simultaneously, or substituting one or the other with a password. As well, there are ways to augment your security through the use of software. Applications like Duo Mobile are able to leverage the biometric data stored on your device as well as trusted devices and users to offer multi-factor authentication.

It goes without saying that one of the biggest draws to biometric authentication is their ease of use. Instead of having to input a password, you simply place a finger on the appropriate sensor or lift the device to your face for quick and easy access. And as biometric security on smartphones continues to get faster, it will continue to be a major draw for consumers.

As for which security method is safest for your device, another reason why it’s difficult to give a definitive answer is because everyone’s situations are different. However, provided that you’re not Beyoncé or Tim Cook, your fingerprint sensor or iris scanner is probably the superior security protocol for the time being, if for no other reason than to mitigate the possibility that someone could guess or watch you type a password. As mentioned previously, neither the biometric nor the non-biometric are infallible, so all we can do is work with what we have at our disposal, being cautious and acutely aware of each security method’s limitations, and wait as they continue to get better over time.

Now I’d like to hear from you. What do you currently use to lock your smartphone? Did this article change your opinion about biometric security or alphanumeric passwords? Will you be using a different method of securing your device? Give us your thoughts and opinions by sounding off in the comments below.