Affiliate links on Android Authority may earn us a commission. Learn more.

3D or not 3D? Is that (yet again) the question?

Published onDecember 26, 2017

This is the first in a three-part series, looking at 3D imaging, including where it’s been in the past, what’s happening now with VR and AR systems, and whether or not we’ll eventually get to the “real” 3D of holographic displays as seen so often in sci-fi.

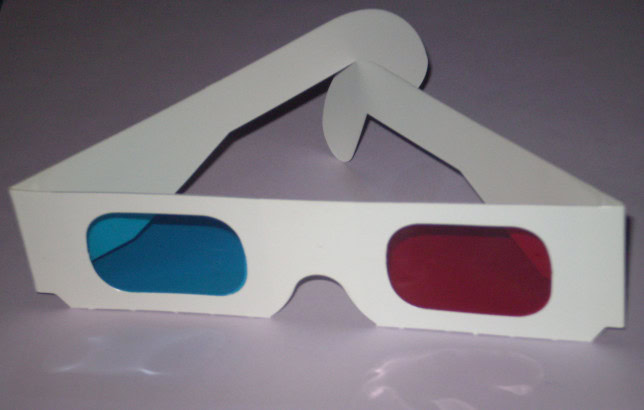

Every few decades the industry goes through a 3D craze. In the 1980s, 3D came to the movies in a slew of action and sci-fi “B” movies, and cardboard glasses. It popped up again in movies in the late 2000s, and there’s been a yearly trickle of 3D releases ever since (though most are conversions of conventionally shot films).

The TV industry went through it just a few years back, bringing a flood of “3D-ready” televisions, despite a notable lack of televised 3D content. Now”4K” is the buzzword of the day in the TV market, and 3D’s started to moving into the mobile market, only under a different name. 3D has come to the smartphone market in the form of “virtual reality.”

Before now the notable characteristic that each and every previous 3D craze has shared is that they all ultimately failed. 3D imaging never managed to live up to the hype and establish itself as the standard in any but a very few, highly specialized applications. 3D movies remain the exception, not the rule; no one is sitting at their TV watching the game through 3D glasses. Why?

The notable characteristic that each and every previous 3D craze has shared is that they all ultimately failed.

Sure, 3D content, whether it’s a film, TV, or game, is more difficult (read: more expensive) to produce than “flat” content, but that’s never really held anything back in the tech industry. If there are customers willing to pay for a given feature, someone will offer it. And that’s where 3D has always fallen short. After an initial flurry of excitement, people just stop buying. I’m a good example; my most recent large-screen TV purchase was touted as “3D ready” and came complete with two pairs of glasses and a “3D” button on the remote. Two years after buying it, the glasses are still in their original box and the “3D” button gets pressed only after the set’s been accidentally switched to that mode, blurring what I’m trying to watch.

Why aren’t people buying? The basic problem is something the entertainment industry seemingly can’t admit: it just doesn’t work. Sure, you can put on the 3D glasses and watch the football game or the swordfight or whatever “spring out of the screen” and take on the illusion of depth. But how long do you want to keep watching that way? If you’re like many people, at least judging from the reported incidences of discomfort, not very long. Even if you don’t mind having to wear the glasses in the first place (they’re not exactly the most convenient thing), the viewing experience just isn’t worth it. After the novelty wears off (which seems to take all of fifteen minutes), you’re faced with the reality that (a) the illusion of depth doesn’t really do all that much in most situations and (b) it’s not worth the headache. Literally.

The problem here is that 3D displays really don’t show images in three dimensions. What we call “3D” is in reality stereoscopic imaging. Your left and right eyes are being shown slightly different pictures, simulating what each would see in a real-world scene. The difference between the two images is what creates the illusion of depth, though there isn’t really any depth to either of the views separately.

Unfortunately, the difference in left-eye and right-eye views is only one of the cues that our visual systems use to detect depth. There are a number of others, such as how objects within the field of view move relative to one another as we move our heads, the different depths to which the eyes have to focus when looking at various objects in a scene, and so on.

With stereo images, we're not sure exactly what's wrong with the scene, but it's pretty obvious that something's not right.

In a stereoscopic image, at least of the sort we see in “3D” movies or television, none of these additional cues are correctly seen. There’s a conflict between what the stereo images are telling us, and what we’re seeing (or rather, aren’t seeing) with respect to these other factors.

Add that images generally aren’t correct for every individual (your eyes probably aren’t exactly the same distance apart as the left and right camera lenses that shot the scene), and the overall experience is less than ideal. We’re not always sure exactly what’s wrong with a scene, but it’s pretty obvious when something’s not right.

Then there’s the problem of keeping the two views separate. To make a stereo display system work, you generally need some way of making a single display device show both the left-eye and right-eye views, and at the same time keep each of the viewer’s eyes from seeing the wrong content! There are several ways to do this, some more successful than others. The old red and blue glasses familiar to fans of 1950s 3-D monster movies and comic books doesn’t work so well with color images.

More recent means of providing this separation include putting LCD shutters in the glasses (showing left-eye and right-eye pictures interleaved at a rate synchronized with the LCDs), and showing the two images through different polarizing filters (matching the polarization of each lens of the glasses). All of these suffer from a loss of brightness relative to what you’d see with a normal 2-D display. None of them perfectly separate the images. A little “left” image almost always sneaks into the right eye, and vice-versa. This can cause a blurry appearance and lead to even more visual fatigue.

Of course, there are ways to get rid of the glasses entirely. “Autostereo” displays work by optically directing the two images of the stereo pair to different points in space. As long as your head is in the proper location, each eye sees (mostly) just the image meant for it. The problem, of course, is that you have to keep your head (or the display) in the right spot, or the stereo illusion is ruined.

Autostereo displays work by directing the two images to different points in space. The problem, of course, is that you do have to keep your head in the right spot.

This method has worked best with smaller displays and especially those in handheld devices. Several smartphone and gaming displays have at least been demonstrated using an autostereo system. Relatively few, notably a couple of LG Optimus models, an HTCEVO, and some Sharp and Hitachi products (mostly in the Japanese domestic market only), have actually been sold commercially.

Stereo display re-entering the mobile market, but in a slightly different form: the virtual reality (VR) headset. Whether as a dedicated device, or the sort of “budget VR” you get by adapting a smartphone (à la Google Cardboard or the raft of smartphone headsets which followed), today’s VR is basically just another take on stereoscopic viewing. It has all the benefits and all the problems (along with some new ones) that the medium’s always had. Right now, VR is generating a lot of buzz, but wether this will finally be what makes 3D a permanent part of the landscape, or just another case of “well, it seemed like a good idea at the time?” That’s the subject of the next article in this series, so stick around.