Affiliate links on Android Authority may earn us a commission. Learn more.

Bring on the camera sensor arms race

Published onJune 13, 2020

Humans are obsessed with miniaturization. We like to make everything smaller. And there’s a reason for that. It makes things lighter, easier to carry, and perhaps most importantly, it makes things marketable. If computers were still the size of large rooms, how many people would be buying them?

While miniaturization works for a lot of products, be it computers, clocks, or even phones, miniaturized cameras are restrained by one particularly frustrating factor: physics.

The reason behind this limitation is fairly simple. More information requires more light. More light requires a bigger sensor. A bigger sensor requires larger hardware. That’s just a fact of life. And because there is so much stuff to pack into a smartphone, the camera part of a phone hasn’t traditionally been able to match the sensor size of a dedicated handheld camera.

As the years have passed, the focus of smartphone marketing has shifted hard towards the camera. People want to document their lives, and having a camera on us everywhere we go has changed how we live. We can shoot, edit, and share directly from one device. That’s powerful.

The hardware enabling this has evolved extremely quickly over the years. Phones went from having a single camera to three or more in just a couple of generations. Now we have ultra-wide and telephoto lenses, depth sensors and color filters. This varies wildly between devices, but the one metric that has been creeping up and up and up is the size of the camera sensor itself.

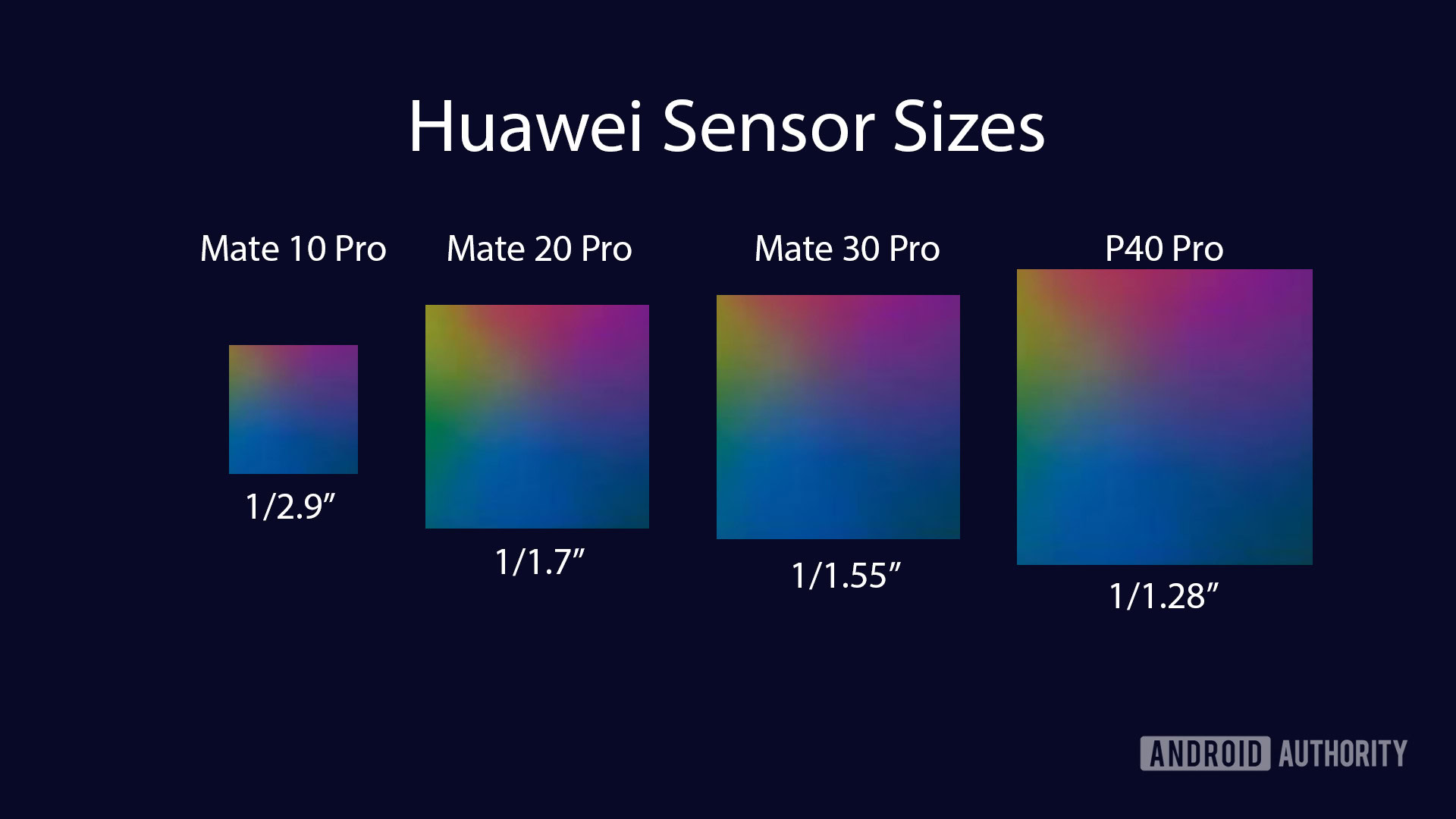

As an example, the HUAWEI Mate 10 Pro from 2017 had a sensor size of 1/2.9-inches. Just three years later, the HUAWEI P40 Pro released with a sensor size of 1/1.28-inches. That’s a huge difference. The P40 Pro sensor is over two times larger, allowing for much more light intake.

But HUAWEI isn’t the only one enlarging its sensors. In fact, in the last couple of years we have seen an all-out arms race for sensor size from key players like Sony and Samsung. And unlike the race to stick as much RAM in a smartphone as possible, sensor size actually matters.

Bigger is better

A couple of weeks ago, vivo unveiled the X50 Pro Plus, a phone with a very, very large primary camera sensor. It’s 1/1.31-inches, larger than that of the Samsung Galaxy S20 Ultra. And, at 50MP instead of 108MP, individual pixel size is much larger, too. This means better image quality at its maximum resolution, and in all likelihood, better image quality at the 12.5MP resolution the phone will likely bin down to.

While the vivo X50 Pro Plus’ isn’t the largest sensor on the market, being barely outshined by HUAWEI’s 1/1.28-inch sensor on the HUAWEI P40 series, an additional giant-sensor phone helps normalize enormous cameras in the smartphone market. Especially since vivo isn’t a market leader like HUAWEI or Samsung.

As phones get bigger, sensors get larger. That's a great thing.

Previously, it seemed impossible to stuff a sensor this large in a phone. Phones were just too small, and focus was put on making devices thinner and thinner. It was hard to make a lens system that didn’t bulge out of the device to an extreme degree. But, as phones have gotten bigger and cameras have gotten more important to users, big camera bumps have started to become both justified and normalized. Instead of looking clunky and out of place, large camera bumps have started to become a sign of a phone’s optical capabilities.

As we’ve seen in phones like the HUAWEI P40 Pro, Samsung Galaxy S20 Ultra and others, bigger sensors really do result in better image quality. You can gather much more light, allowing for higher shutter speeds and lower ISO values. Size really does matter. And smartphones have another advantage that can take even better advantage of those sensors — computational photography.

Computers + physics = 💖

Smartphones are computers first, cameras second. Because of this, they’ve rapidly become faster, better, and smarter. Companies like Google have learned how to cheat physics with computational imaging and big data, and HUAWEI has used incredibly good hardware with killer software to make amazing camera experiences. Combine these computational photography features with the ever-improving lenses and sensors, and we’re quickly starting to see better smartphone cameras than we thought possible even a few years ago. This spells even more trouble for the already-troubled handheld camera industry.

Most dedicated cameras don’t have much in terms of computational imaging features. While some camera OEMs have just started to integrate things like smart HDR, smartphones have had this for years. Fans have been calling for Google to introduce a dedicated Pixel camera ever since the first Pixel phone came to market, and there’s good reason for that. Smartphones are just, well, smarter.

If computational imaging joins forces with raw physics, photography will change forever.

Phones already have the capability to do things like semantic segmentation, object detection, automatic astrography mode and more. They have been trained on massive data sets for years, while camera companies just haven’t kept up. Add that to the fact that UX design on a smartphone is way better than most dedicated cameras, and you’ve got a device that far outshines traditional cameras in multiple categories.

A huge sensor sitting alongside computational smarts isn’t far off. The big milestone for a smartphone sensor size is 1-inch, since that’s the same size many dedicated pocketable cameras use. A smartphone with a 1-inch sensor, combined with the computational smarts invented over the past few years, will change the world forever. I wouldn’t be surprised if we saw it in the next year or two.