Affiliate links on Android Authority may earn us a commission. Learn more.

Is the cost of phone privacy worth paying?

When Apple and Google announced, around a year ago now, that they would start encrypting smartphones by default there was an angry reaction. It would be fair to say that not everyone in law enforcement and the legal establishment, not to mention the government, believes that the right to personal privacy should outweigh their ability to access information they deem necessary in the fight against crime and terrorism.

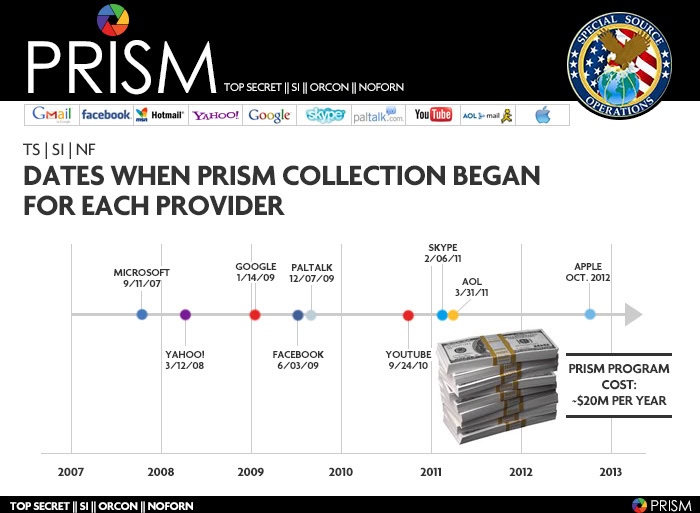

It shouldn’t have been a major surprise, in the aftermath of Snowden’s revelations and the storm surrounding PRISM, to find the big tech companies looking for a way out. People were generally alarmed at the invasion of privacy, the widespread snooping, and the prospect that their tech companies had been complicit in it. By employing default decryption they removed themselves from the tricky position of having to unlock users’ phones when compelled to do so by law enforcement or government agencies.

Google and Apple do not have the passcodes to access user devices, they simply aren’t stored by the companies anymore, and so, unless they’ve stored data in the cloud or through other services off the phone, all the photos, documents, emails, and anything else on the device are effectively inaccessible.

What’s the problem?

There has been a string of inflammatory comments, op-eds, interviews, and general propaganda since then from the FBI, NSA, the legal establishment, and the police force, seeking to paint Google and Apple as the bad guys for protecting customer privacy. FBI Director, James Comey, was particularly outspoken saying, “…encryption threatens to lead us all to a very, very dark place.”

The FUD campaign has cast encryption as the friend of the pedophile, terrorist, and murderer.

In a nutshell, the argument goes that bad guys are harder to prosecute because their phones can’t be accessed. The FUD campaign has cast encryption as the friend of the pedophile, terrorist, and murderer. They seem to be building a head of steam to try and push through legislation that will force tech companies to create backdoors for law enforcement.

The opinion piece in the NY Times recently is a perfect example. Penned by a couple of prosecutors, a DA, and a police commissioner, it suggests that smartphone encryption is the reason murders are going unsolved. The condemnation is strong, “…our agencies rely on evidence lawfully retrieved from smartphones to fight sex crimes, child abuse, cybercrime, robberies or homicides. Full-disk encryption significantly limits our capacity to investigate these crimes and severely undermines our efficiency in the fight against terrorism. Why should we permit criminal activity to thrive in a medium unavailable to law enforcement?”

Is anyone buying this?

Sadly, a lot of people probably are. How can anyone argue against making it easier to catch criminals? But this comes dangerously close to saying that if you don’t have anything to hide, you don’t have anything to fear. Why would you worry about it if you aren’t involved in crime or terrorism? After all, they insist they’ll only use these backdoors when they have a “judicial determination of good cause.”

Where have we heard that before? The prosecutors, DAs, and police very probably mean what they say, but that doesn’t mean other government agencies will abide by their standards. They haven’t in the past. There are also a lot of other reasons why it would be dangerous to reverse encryption, seek to outlaw it, or insist upon the creation of backdoors.

Backdoors are a bad idea

This article by Golden Frog president (providers of the VyprVPN service), outlines the counter-arguments nicely.

Experts have roundly criticized the idea that you can create backdoors without increasing the risk of security flaws and technical vulnerabilities. Take a look at this report from some of the most respected computer security experts around. It would increase the risk of exposing us all to action from hostile governments, terrorists, and cybercriminals.

Where do we stop?

How will authoritarian governments use it? What about the impact on human rights? How will private companies looking to safeguard their data feel about it?

Law enforcement has never had it so good anyway. The amount of data they have access to is greater than at any time in human history. Georgia law professor, Peter Swire, calls it The Golden Age of Surveillance.

The price is worth paying

The idea that it will be easier to prosecute criminals has to be weighed against what we’re giving up. It would be easier to prosecute criminals if we had security cameras in every room. It would be easier to prosecute criminals if law enforcement didn’t need warrants. That argument in itself isn’t enough. You also can’t take it in isolation. If you uphold the principle that they should have access to phones, then why not our entire digital lives?

People have a right to protect their privacy. Whether their fears are based on greedy corporations data mining and profiling, government agencies surveilling them, or criminals stealing their identities, there are plenty of reasons, beyond being a criminal, to want to protect your privacy. Arguing in favor of privacy is not about creating safe havens for criminals, or even mistrust of law enforcement, it goes deeper than that.

In the words of Supreme Court Justice, Louis Brandeis, “Experience should teach us to be most on our guard to protect liberty when the government’s purposes are beneficent. Men born to freedom are naturally alert to repel invasion of their liberty by evil-minded rulers. The greatest dangers to liberty lurk in insidious encroachment by men of zeal, well-meaning but without understanding.”