Affiliate links on Android Authority may earn us a commission. Learn more.

What caused the great Galaxy Note 7 defect? Here are the leading theories (UPDATE: Samsung explanation coming)

Published onOctober 12, 2016

What went wrong? Will this be a problem in future Samsung handsets? We hope not, but we should know all the details "in the coming weeks", when Sammy promises to release more information on their findings.

The replacement phones have batteries from a separate and different supplier than the original Note 7 devices. We’re currently conducting a thorough investigation, and it would be premature to speculate on outcomes. We will share more information in the coming weeks.

Original, October 12 9:40 – With the end of Galaxy Note 7 production and the second recall echoing around the global media, it’s going to take Samsung some time to shake the damage that’s been done to its manufacturing reputation. With the first recall now clearly failing to address the Note 7 defect, there are a lot of questions to be answered about exactly what went wrong with the handset.

Samsung is still investigating the latest causes of Galaxy Note 7 fires, and we may never know the full story behind what is sure to be seen at the greatest blunder in smartphone history. Still, a few sources are already speaking out about the most likely factors behind these infamous fires and explosions.

Bad batteries

After the first explosion reports, Samsung engineers concluded that the defect had be caused by defective batteries from one or more of the companies suppliers. More specifically, the company believed that these bad batteries had been designed by its own Samsung SDI division, and that it would be safe to use batteries from its alternative supplier Amperex Technology Ltd (ATL).

The Samsung SDI designed batteries, which were manufactured in Vietnam and South Korea, were said to suffer from a manufacturing fault that could lead to a short circuit within the cell. If even a small short occurs within a lithium-ion battery, thermal runaway can cause the cell to continue to heat up, eventually leading to a fire or explosion.

A new report by investigators points to similar manufacturing defects with ATL batteries as well

Samsung estimated that one in every 42,000 handsets suffered from the manufacturing fault. The first global recall was initiated to replace 2.5 million handsets equipped with potentially defective batteries with newly manufactured handsets with ATL cells. Unfortunately, this recall hasn’t stopped reports of exploding handsets coming in, leading to a full stop on Galaxy Note 7 production.

A new report by investigators, seen by Bloomberg, points to similar manufacturing defects with the ATL batteries, which were supposed to be safe. The issue apparently crept into the supply line after Samsung began replacing the Note 7, but it’s unknown how many devices are affected. As a result, Samsung is recalling the 190,984 Note 7s that it sold in China as well.

Not enough space

In addition to the battery manufacturing problem, an unpublished preliminary report by Korea’s Agency for Technology and Standards revealed that the company may have made a handset manufacturing error that “placed pressure on plates contained within battery cells.”

The additional tension placed on the battery in models affected by the sub-optimized assembly could have led to the negative and positive poles coming into contact with each other, resulting in a battery breakdown and fires. This problem may have been compounded by an insufficient layer of insulation between the positive and negative sides of the battery, which may crack or puncture under the additional pressure. In other words, the limited space inside the chassis may have bent and cracked the inside of the batteries.

Lithium-ion batteries found in today’s smartphones are already densely stacked in layers to maximise battery capacity, but there’s still a lot of competition for space inside handsets. Given the huge number of features packed inside the Galaxy Note 7, including wireless charging circuitry, processor cooling pipes, and the new iris scanner, it’s not difficult to believe that there was very little room for manufacturing errors in terms of internal space.

According to a person familiar with discussions between government agencies and Samsung, the SDI batteries from the first batch of Note 7s were indeed too large for the handset. Perhaps Samsung’s should have abandoned the 3.5mm jack for a few extra square millimeters…

With reports of phones catching fire while turned off or unplugged, faulty batteries certainly sound like a possible cause. Although this theory doesn’t fully explain why most reports of fires happened while the phone was part way through charging.

The demand for faster charging

The Note 7 defect is now also reportedly linked to Samsung’s fast charging technology too. According to a Financial Times source who has spoken to Samsung executives, problems with the phone may have arisen from adjustments made to the processor in order to speed up battery charging times.

“If you try to charge the battery too quickly it can make it more volatile. If you push an engine too hard, it will explode. Something had to give. These devices are miracles of technology — how much we can get out of that tiny piece of lithium-ion,”

Unfortunately, the source doesn’t make it entirely clear how this type of problem would have come about, or how changes made to the processor would affect the charging circuitry used to monitor and charge the li-ion battery.

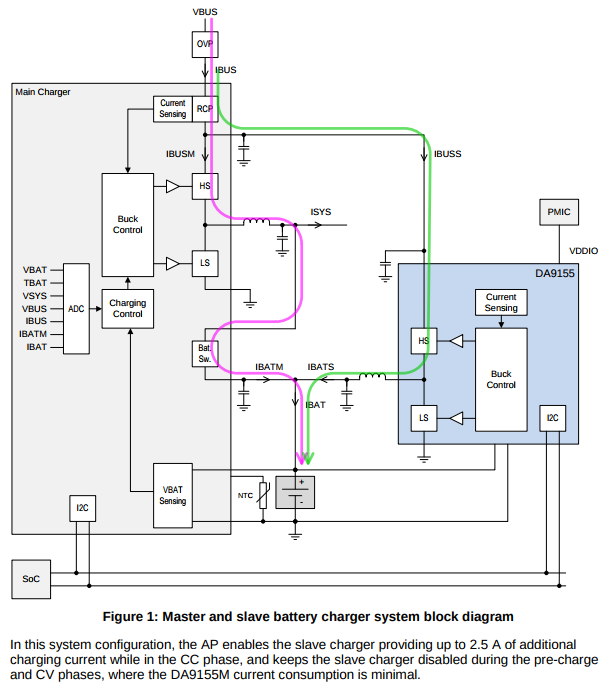

However, a little digging through a ChipWorks teardown reveals the use of a Dialog DA9155 charging chip, alongside the familiar MAXIM power IC. Importantly, this DA9155 does not appear to be found inside the Galaxy S7 or S7 edge. This chip is a slave charger that extends the current capabilities of a master power IC for increased charging currents up to an additional 2500mA. It’s controlled by the application processor (AP) and, interestingly, kicks in during the high-power constant current charging stage.

A read through the datasheet reveals that this chip features an AP programmable output current, switching frequency, and temperature monitor. As a slave device, programming and controlling the current and cooling is all left to the AP, which Samsung would have to program itself.

Careful consideration has to be made not to exceed the battery’s charging current, optimize the switching frequency to the inductor charging circuitry for efficient power transfer, and monitoring the temperature of the battery. Furthermore, the DA9155M doesn’t force a chip reset until TJUNC_CRIT is triggered at 140°C, so it’s up to the AP and Samsung’s programmers to monitor lower temperatures and adjust power delivery.

Of course, we don’t know how Samsung programmed its AP and this chip to control the battery charging characteristics, but it’s possible that engineers may have been using this IC to push the handset’s fast charging capabilities to the battery’s limits. Although this does raise the question of why this type of problem couldn’t have been addressed with a firmware update, either by lowering the chip’s current output or switching it off altogether.

That’s just my own speculation based on the FT article though, it’s possible that the source is alluding to other changes made to Samsung’s power management algorithms, the temperature monitoring system, or one of the other four PMIC components found inside the Note 7, which could be used to improve fast charging times.

It’s certainly possible that fast charging power management is just another contributing factor to a broader battery issue and this information certainly goes some way to explaining why Samsung has halted production. This type of problem can’t be fixed by simply exchanging batteries, it’s a deeper fault located inside Samsung’s electronic hardware design.

A combination of factors

Despite weeks of testing, Samsung’s engineers have still not been able to repeatedly reproduce the fires and explosions, according to a report in the New York Times. It appears that the company cannot be sure exactly what the cause of the problem is, suggesting that the defect may not lie with any one individual component.

“[Samsung] was too quick to blame the batteries; I think there was nothing wrong with them or that they were not the main problem,” – Park Chul-wan, former director of the Center for Advanced Batteries at the Korea Electronics Technology Institute

Allegedly, the corporate structure within the company has not helped sort out the problem either. Two former Samsung employees, who asked not to be named for fear of retaliation, described the workplace as militaristic, with orders coming from higher management who didn’t necessarily understand the actual technologies inside the product. Furthermore, Samsung told employees to keep all communications about its Note 7 tests offline, meaning that information exchanges between testers were severely hampered.

Samsung may have done the right thing by initiating a full recall and ending production of a handset with faults that still aren’t fully understood. However, there will now always be the lingering suspicion that the company may have been able to salvage the Note 7, had it taken more time to ensure that the first recall solved the issue.

It could take weeks, even months before Samsung and regulatory investigators understand the full cause, or causes, behind the various Galaxy Note 7 fires. We will just have to wait and see if Samsung ever officially reveals the defect that toppled the company’s otherwise greatest piece of mobile engineering.