Affiliate links on Android Authority may earn us a commission. Learn more.

Up close and personal: how the Samsung Galaxy S6 uses its octa-core processor

Published onJune 22, 2015

One caveat from this research was that I hadn’t yet had the chance to run my tests on a Cortex-A53/Cortex-A57 setup as my octa-core test device had a Qualcomm Snapdragon 615, which has a quad-core 1.7GHz ARM Cortex A53 cluster and a quad-core 1.0GHz A53 cluster. However I have now had the opportunity to run some tests on a Samsung Galaxy S6 and its Exynos 7420 processor!

Recap

So to recap briefly what this is all about. Smartphone have multi-core processors. First it was dual-core, then quad-core and now we have 6 and 8 core mobile processors. This is also true in the desktop space, however there is one big difference between the 6 and 8 core desktop processors from Intel and AMD, and the 6 and 8 core processors based on the ARM architecture – most ARM based processors with more than 4 cores use at least two different core designs.

This arrangement is known as big.LITTLE, where big processor cores (Cortex-A57) are combined with LITTLE processor cores (Cortex-A53).

Once you have a multi-core setup, the question arises, can Android apps use all those cores effectively? At the heart of Linux (the OS kernel used by Android) is a scheduler which determines how much CPU time is given to each app and on which CPU core it will run. To utilize multi-core processors fully, Android apps need to be multi-threaded, however Android is itself a multi-process, multi-tasking OS.

One of the system level tasks in Android’s architecture is the SurfaceFlinger. It is a core part of the way Android sends graphics to the display. It is a separate task that needs to be scheduled and given a slice of CPU time. What this means is that certain graphic operations need another process to run before they are complete.

Because of processes like the SurfaceFlinger, Android benefits from multi-core processors without a specific app actually being multi-threaded by design. Also because there are lots of things always happening in the background, like sync and widgets, then Android as a whole benefits from using a multi-core processor.

For a much fuller explanation of multi-tasking, scheduling, and multi-threading please read Fact or Fiction: Android apps only use one CPU core.

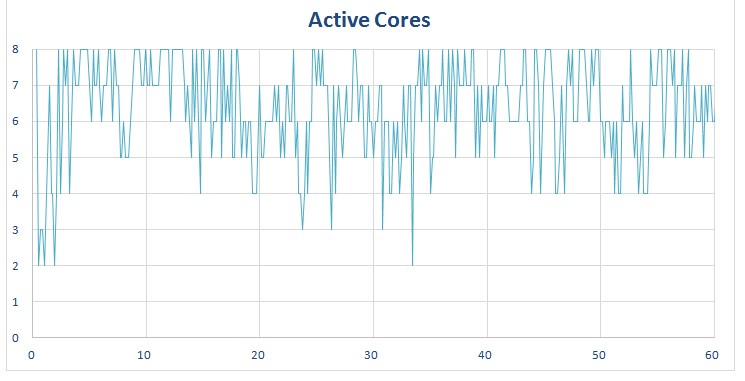

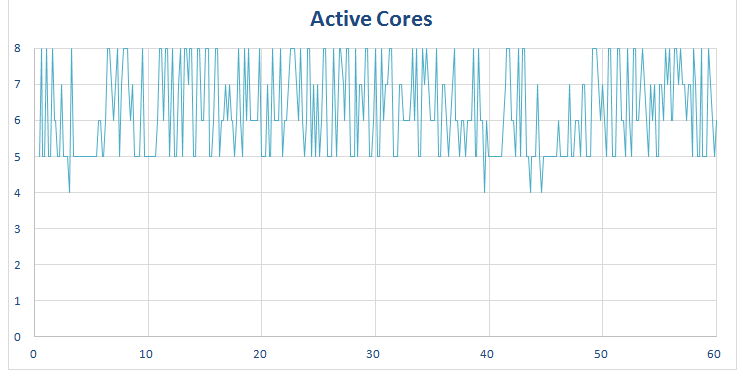

Here are a couple of the key graphs from my previous study, which show clearly that Android is able to use more than one CPU core:

The two graphs show the number of cores being used, and the core percentage usage, while using Chrome on a smartphone with an octa-core Snapdragon 615.

As you can see, seven cores are consistently being used with the occasional spike to 8, and a few times when it dips to 6 and 4 cores. You will also notice that there are two or three cores which run more than the others, however all the cores are being utilized in some way or another.

What we are seeing is how the big.LITTLE architecture is able to swap threads from one core to another depending on the load. Remember, the extra cores are here for energy efficiency, not performance.

Samsung Galaxy S6

The graphs above are for a device with a Qualcomm Snapdragon 615, which has a quad-core 1.7GHz ARM Cortex A53 cluster and a quad-core 1.0GHz A53 cluster. Although the two clusters of cores are different, one is clocked at 1.7GHz and the other at 1GHz, the difference between the two is mainly just clock speed.

The Exynos 7420 used in the Galaxy S6 uses four ARM Cortex-A57 cores clocked at 2.1GHz, and four Cortex-A53 cores clocked at 1.5GHz. This is quite a different setup than the Snapdragon 615. Here there are two distinctively different CPU core architectures being used together. For example the Cortex-A57 uses an out-of-order pipeline, while the Cortex-A53 has an in-order pipeline. There are of course many other architectural differences between the two core designs.

The Exynos 7420 used in the Galaxy S6 uses four ARM Cortex-A57 cores clocked at 2.1GHz, and four Cortex-A53 cores clocked at 1.5GHz.

It is also worth noting that the max clock speed for the Cortex-A53 cores is 1.5GHz, almost as high as the bigger of the Cortex-A53 clusters in the Snapdragon 615. What this means is that the overall performance characteristics will be quite different on the Exynos 7420. Where the Snapdragon 615 may have favored the big cluster (Cortex-A53 @ 1.7GHz) for some workloads, the Exynos 7420 could favor the LITTLE cluster (Cortex-A53 @ 1.5GHz) as it is almost as powerful as the big cluster in the Snapdragon 615.

Chrome

So let’s start by comparing the way the Samsung Galaxy S6 uses Chrome. To perform the test I opened the Android Authority website in Chrome and then started browsing. I stayed only on the Android Authority website, but I didn’t spend time reading the pages that loaded, as that would have resulted in no CPU use. However I waited until the page was loaded and rendered, and then I moved on to the next page.

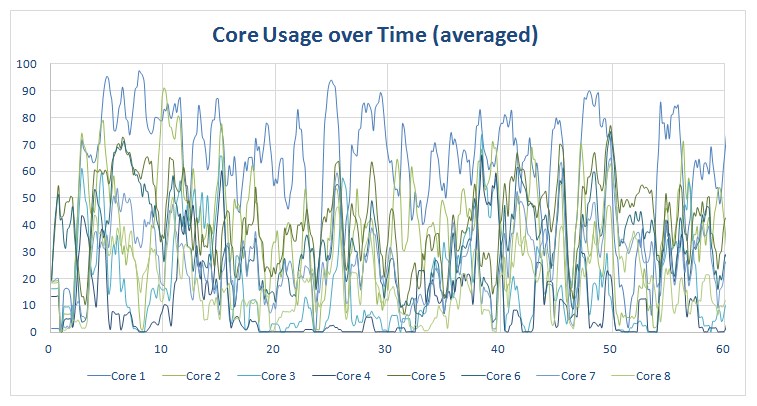

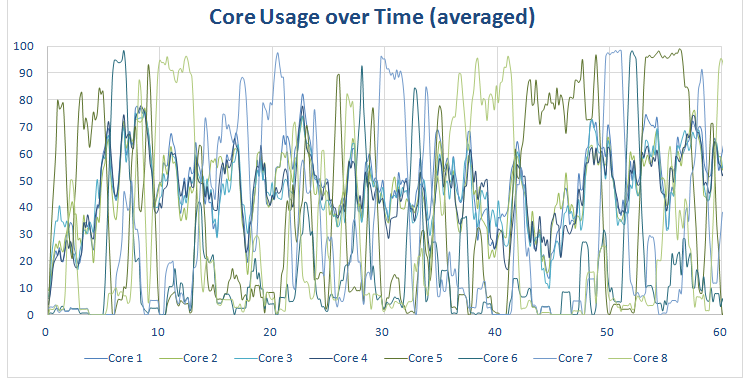

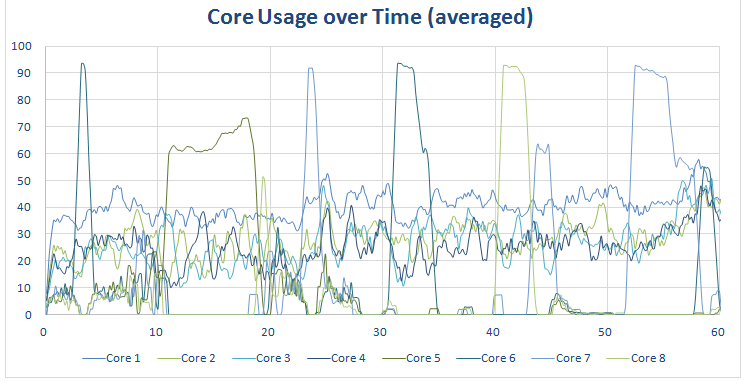

The graph above shows how many cores are being used by Android and Chrome. The baseline seems to be around 5 cores and it peaks frequently at 8 cores. It doesn’t show how much the core is being used (that comes in a moment) but it shows if the core is being utilized at all.

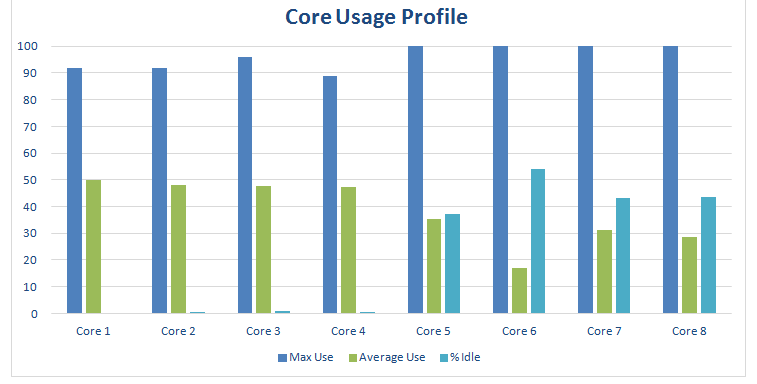

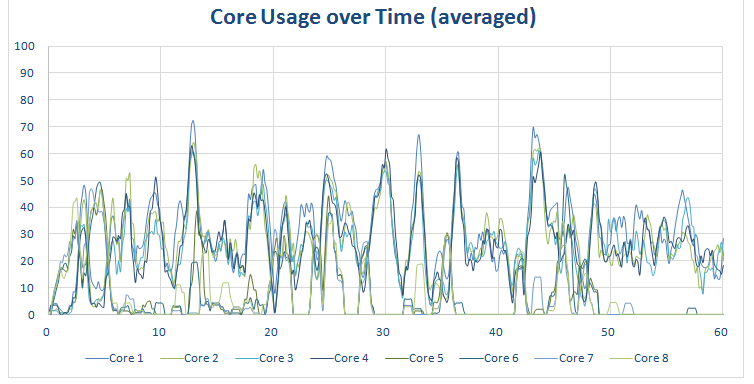

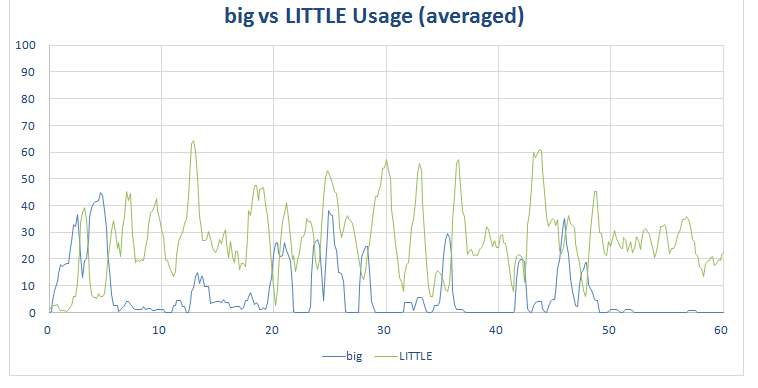

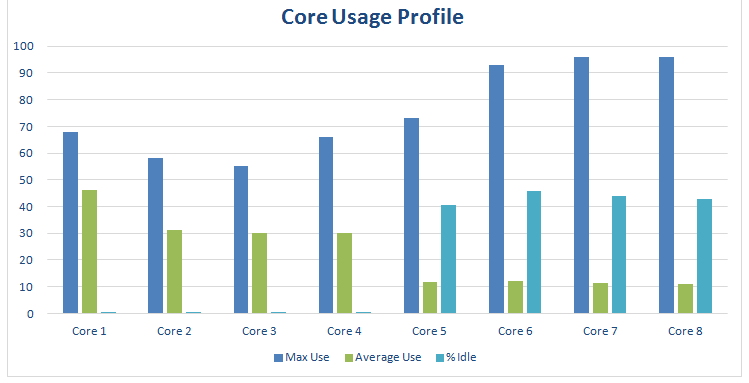

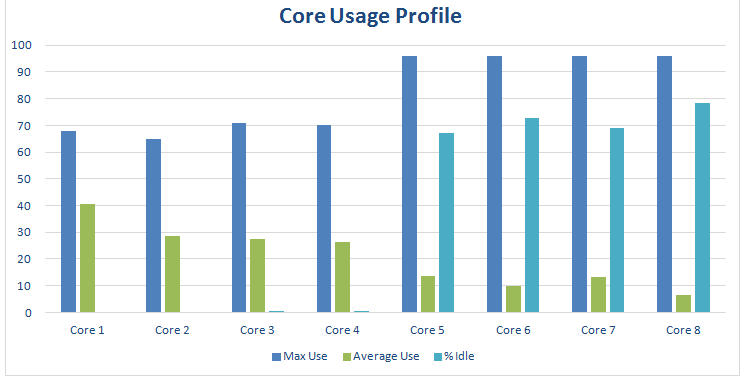

The graph above shows how much each core was utilized. This is an averaged-out graph (as the real one is a scary scrawl of lines). This means that the peak usages are shown as less. For example, the peak on this graph is just over 95%, however the raw data shows that some of the cores hit 100% multiple times during the test run. However it still gives us a good representation of what was happening.

On the Exynos 7420 (and on the Snapdragon 615) cores 1 to 4 are the LITTLE cores (the Cortex-A53 cores) and cores 5 to 8 are the big cores (the Cortex-A57 cores). The graph above shows that the Exynos 7420 is favoring the little cores and leaving the BIG cores idle as much as possible. In fact the little cores are hardly ever idle were as the BIG cores are idle for between 30% to 50% of the time. The reason this is important is because the BIG cores use more battery. So if the more energy efficient LITTLE cores are up to the task then they are used and the big cores can sleep.

However when the workload gets tough the big cores are called into action, that is why the max usage for the big cores is at 100%. There were times when they were used at 100% and other times when there were idle, allowing the LITTLE cores to do the work.

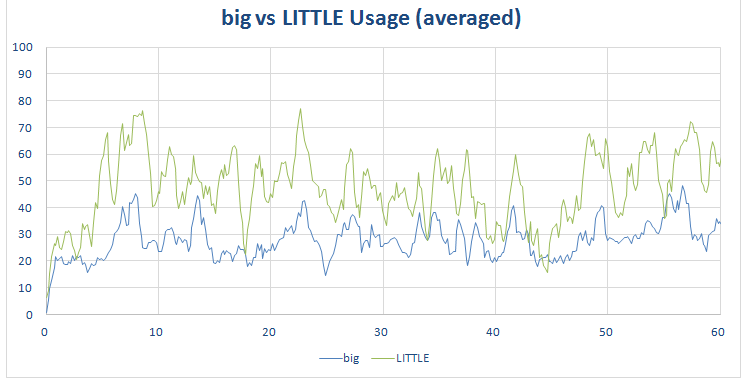

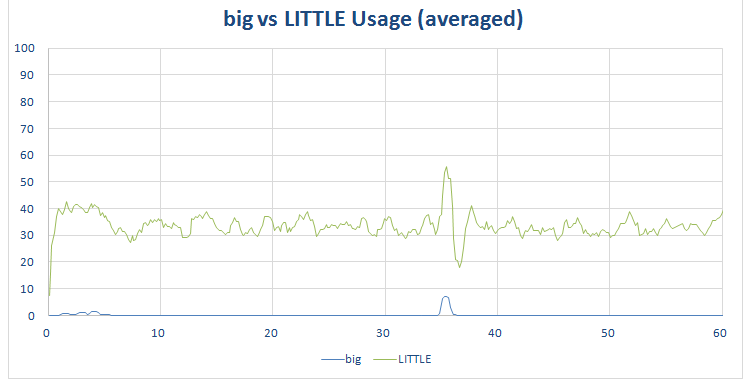

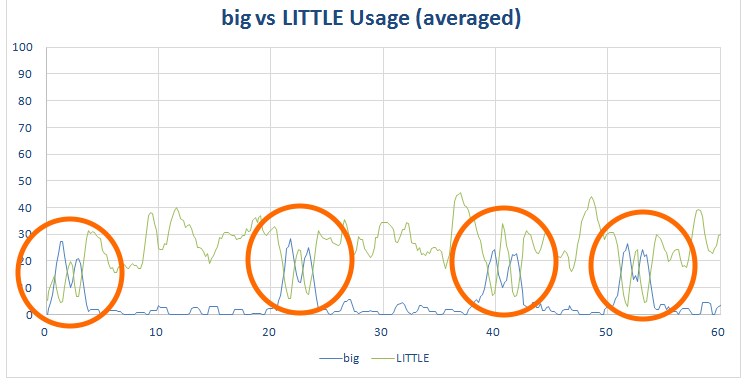

The graph above shows this more clearly. The green line shows the combined LITTLE core usage, while the blue line shows the combined big core usage. As you can see the LITTLE cores are being used all the time, in fact the LITTLE core usage only occasionally dips below the big core usage. However the big cores spike as they are used more and dip when they are used less, only coming into play when needed.

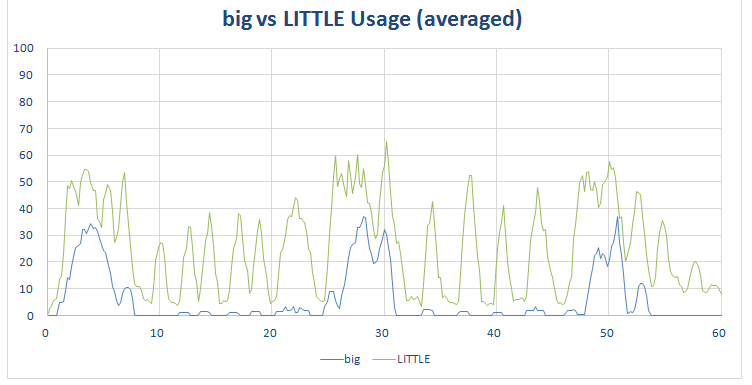

The workload is artificial in the sense that I don’t stop and read any pages, as soon as the page was loaded I moved on to the next page. However the next graphs show what happens if I loaded a page, read some of it, scrolled down a little, read some more, finally I clicked on a new link and started the process again. In the course of 1 minute I loaded three pages. These can be clearly seen here:

Notice the three spikes in big core usage as I loaded a page and the spikes in the LITTLE core usage as I scrolled down the page and new elements were rendered and displayed.

Gmail and YouTube

Google deploys many of its key Android apps via the Play Store, and besides Chrome, other popular Google apps include YouTube and Gmail. Google’s email client is a good example of an app that uses Android’s user interface elements. There are no sprites, no 3D graphics, no video to render, just an Android UI. I performed a general usage test where I scrolled up and down in the inbox, searched for emails, replied to an email and wrote a new email – in other words I used the app as it was intended.

As you would expect, an email client isn’t going to stress a processor like the Exynos 7420. As you can see from the graph, overall CPU usage is fairly low. There are a few spikes, but on average the cores utilization is less than 30 percent. The scheduler predominantly uses the LITTLE Cortex-A53 cores and the big cores are idle for around 70 percent of the time.

You can see how the LITTLE cores are used more often than the big cores from this graph:

YouTube is different to Gmail in that while it has UI elements, it also has to do a lot of video decoding. Most of the video work won’t be handled by the CPU, so its job is predominately UI and networking plus general coordination.

The big vs LITTLE graph is quite revealing here:

The big cores are hardly being used at all and the energy efficient (but lower performance) cores are being used to move around data, and handle the network connections etc.

Gaming

Games are a quite different category of app. They are often GPU intensive and not necessarily CPU bound. I tested a range of games including Epic Citadel, Jurassic World, Subway Surfer, Crossy Road, Perfect Dude 2, and Solitaire.

Starting with Epic Citadel, the demo app for the Unreal Engine 3, what I discovered is that again the LITTLE cores are being used consistently and the big cores are being used as support, when necessary. On average the LITTLE cores are running at around 30 to 40 percent utilization while the big cores are being used at less than 10 percent. The big cores are idle for around 40 percent of the time, however when used they can peak at over 90 percent usage.

The graph above are for actual game play (i.e. walking around the Epic Citadel virtual world using the on screen controls). However Epic Citadel also has a “Guided Tour” mode which automatically swoops around various parts of the map. The core usage graph for Guided Tour mode is slightly different to the real game play version:

As you can see, the Guided Tour mode has several spikes of CPU activity, which the real game play version doesn’t. This emphasizes the difference between real world workloads and artificial workloads. However, in this particular case, the overall usage profile isn’t altered much:

Here are the graphs for Solitaire, Jurassic World, Subway Surfer, Crossy Road, and Perfect Dude 2:

As you would expect Solitaire doesn’t use much CPU time, and interestingly Jurassic World uses the most. It is also worth looking at the big versus LITTLE graph for Perfect Dude 2, it shows a near textbook scenario where the LITTLE cores throttle down, while the big cores ramp up. Here is the same graph with those big core peaks highlighted:

Odds and ends

I have two more sets of graphs to complete our picture. The first is a snapshot of the device when idle, with the screen off. As you can see there is still some activity, this is because the program which collects the data itself uses the CPU. In a quantum-physics-esque kind of way, the act of observation alters the outcome! What it does give us is a baseline:

The other set of graphs is the artificial workload created by benchmarks, in this case AnTuTu:

Even a cursory look shows that the workloads generated by AnTuTu are nothing like real world workloads. The graphs also show us that it is possible to get the Samsung Galaxy S6 to max-out all eight of its CPU cores, but it is completely artificial! For more information about the dangers of benchmarks see Beware of the benchmarks, how to know what to look for.

I also need to list some caveats here. The first thing to underline is that these tests do not benchmark the performance of the phone. My testing only shows how the Exynos 7420 runs different apps. It does not look at the benefits or drawbacks of running parts of an app on two cores at 25% utilization, rather than on one core at 50%, and so on.

Secondly, the scan interval for these statistics is around one six of a second (i.e. around 160 milliseconds). If a core reports its usage is 25% in that 160 milliseconds and another core reports its usage is 25% then the graphs will show both cores running simultaneously at 25%. However it is possible that the first core ran at 25% utilization for 80 milliseconds and then the second core ran at 25% utilization for 80 milliseconds. This means that the cores were used consecutively and not simultaneously. At the moment my test setup doesn’t allow me any greater resolution.

On phones with Qualcomm Snapdragon processors it is possible to disable CPU cores by using Linux’s CPU hotplug feature. However, to do so, you need to kill the ‘mpdecision’ process otherwise the cores will come back online again when the ‘mpdecision’ process runs. It is also possible to disable the individual cores on the Exynos 7420 however I can’t find the equivalent of ‘mpdecision’ which means that whenever I disable a core it get re-enabled after only a few seconds. The result is that I am unable to test the workloads, performance and battery life with different cores disabled (i.e. with all the big cores disabled, or with all the LITTLE cores disabled).

What does it all mean?

The idea behind Heterogeneous Multi-Processing (HMP) is that there are sets of CPU cores with different energy efficiency levels. The cores with the best energy efficiency don’t offer the highest performance. The scheduler picks which cores are the best for each workload, this decision making process happens many times per second and the CPU cores are activated and deactivated accordingly. Also the frequency of the CPU cores is controlled, they are ramped up and throttled down according to the workload. This means the scheduler can pick between cores with different performance characteristics and control the speed of each core, giving it a plethora of choices.

The default behavior of a big.LITTLE processor is to use its LITTLE cores.

What the above testing shows is that the default behavior of a big.LITTLE processor is to use its LITTLE cores. These cores are running at lower clock frequencies (compared to the big cores) and have a more energy efficient design (but at the loss of top end performance). When the Exynos 7420 needs to perform extra work then the big cores are activated. The reason for this isn’t just performance (from the user’s point of view) but there are power savings to be found when a CPU core can perform its work fast and then return to idle.

It is also obvious that at no time is the Exynos 7420 being asked to work overly hard. Jurassic World pushes the processor harder than any of the other apps or games, however even it still leaves the big cores idle for over 50 percent of the time.

This raises two interesting questions. First, should processor makers be looking at other HMP combinations, other than just 4+4. It is interesting that the LG G4 uses a hexa-core processor rather than an octa-core processor. The Snapdragon 808 in the LG G4 uses two Cortex-A57 cores and four A53 cores. Secondly, the power efficiency and performance of the GPU shouldn’t be underestimated when looking at the overall design of a processor. Could it be that a lower performing CPU with a more powerful GPU is better combination?

What are your thoughts on Heterogeneous Multi-Processing, big.LITTLE, octa-core processors, hexa-core processors, and the Exynos 7420? Please let me know in the comments below.