Affiliate links on Android Authority may earn us a commission. Learn more.

The 'Google sharing bandwidth' and CBRS story: What's actually happening in the wireless space

April 12, 2018

Wireless spectrum is in high-demand in the U.S., and for good reason. 5G is just over the horizon, and carriers need low-latency, high-bandwidth frequencies. It’s not cheap, either.

The wireless industry is built on high-priced auctions for chunks of spectrum in different parts of the nation, with billions paid to the FCC to gain access.

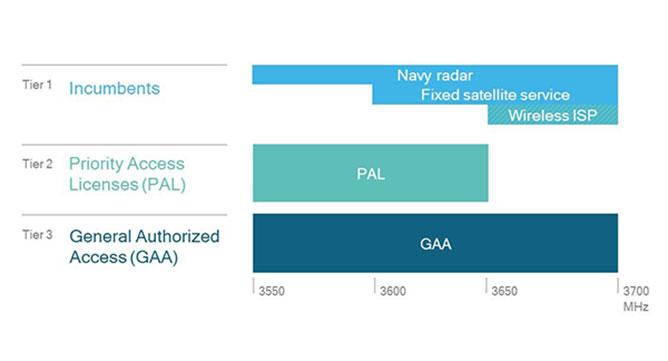

Not all of the spectrum is being used, and shake-ups are happening now and in the near-future. One significant new part of the spectrum to be opened up was announced in 2015, as a future release by the FCC. 150MHz of spectrum between the 3550-3700MHz band, also known as the 3.5GHz Band, and called the Citizens Broadband Radio Service (CBRS).

Previously for the military-only, the attractive CBRS band will be opened up

This very useful band was previously exclusively under military control. The military will still get priority access to CBRS, only now as part of a three-tier framework that will make it available for a variety of commercial uses.

At Mobile World Congress, all the major carriers discussed CBRS with the press, each other, and a number of start-ups hoping to use CBRS for 5G-led innovations and technologies. The same frequency range is being used elsewhere in the world for 5G, and it’s a solid midband spectrum to utilize for this.

Read next: How is 5G actually going to work?

The major carriers are already testing in CBRS frequencies, applying for special licenses to test to better understand propagation characteristics and to see what the band may be able to offer consumers.

One hitch is that the final rules around CBRS and each tier of use are not yet known. The spectrum assignments will be very different to what is currently being used though. CBRS will feature three tiers of use.

The top-tier will remain for military use when it needs, as the incumbent in the channel.

The next tier down will be priority spectrum that is sold at auction, known as Priority Access Licenses (PAL).

The third tier is interesting and set as a General Authorized Access (GAA) portion, which allows for 80MHz of the 3.5GHz band to be more freely used. It is licensed “by rule,” which means any entity with an FCC license may use FCC-authorized telecommunications equipment in the band, without a license for the spectrum.

GAA operators receive no interference protection, so it’s a kind of free for all, but to be clear, auctions are not a part of the GAA setup. It’s rare to get spectrum without having to pay, so it’s no doubt exciting for carriers and other operators, and it is understood that CBRS doesn’t need a clear line-of-sight between a device and a broadcast tower, whereas higher-frequency bands do require this. Wi-Fi bands are an example of regulated but not owned spectrum, which allowed tremendous innovation and improvements to computer and device connectivity.

Google is involved, and that's a key development for disruption

What’s driven fresh interest in CBRS is Google’s involvement. We’ve known Google has been agitating to ensure the FCC sticks to it original rules for CBRS, and doesn’t cave to the big carriers, who want to keep the playing field skewed to their advantage (more on that in a bit).

A Bloomberg article last week added some more fuel to fire to make CBRS cool again, pointing to the Google-led push to aid spectrum sharing. Google is working with other companies, including Federated Wireless, to build sensors, databases, and systems to better deal with interference of all kinds — from trees and obstacles to when the 3.5GHz spectrum must be left to the military. It’s all about sharing the spectrum to allow operators to provide 5G fiber-like speeds, while upsetting the incumbents’ services as well.

Here’s how Bloomberg describes the potential interactions that could take place:

Imagine you’re on a call with your smartphone in Los Angeles and it’s using CBRS to connect you. An aircraft carrier churns past. Systems run by Google, startup Federated Wireless or a few other companies, will spot that, give the Navy a prime bit of the spectrum to use, then move you onto a slightly different channel without dropping the call. When the ship leaves the area, the Navy’s spectrum is sent back into the mix. There’s enough spectrum to go round — 150MHz is the largest chunk of contiguous airwaves to be released in years. And the Navy is unlikely to sail past Denver, Kansas City or most other U.S. locations.

Google and its partners are leading the charge to make GAA more useful by reducing interference. Despite the benevolence Bloomberg’s headline indicates, Google’s involvement no doubt means it will make some serious money off the venture.

The carriers sense disruption. They sense Google moving in on their turf beyond its initial Project Fi foray. To fight back, they are appealing to the FCC to have the coming PAL bands take up more of the spectrum.

CBRS is still some distance away, probably further than the first 5G hotspots, which will emerge as early as this year in some limited areas. The inertia (money) required to get the ball rolling is significant and, as Deutsche Telekom noted at MWC 2018, no one’s made a real business case for 5G yet. Even with 3GPP ratifying a 5G standard, we may be waiting well beyond 2020 to see both handsets and carriers supporting CBRS.

Still, a report by industry research firm Mobile Experts estimated 750,000 CBRS access points will be shipped by 2022. The firm also suggested costs for CBRS networks should be much lower than licensed LTE and distributed antenna system alternatives, due to the nature of spectrum sharing across the three tiers. 5G capabilities are also more attainable than mmWave technology, which requires significantly more and new infrastructure. It’s likely we’ll see a smartphone with 5G in the 3.5GHz band as opposed to the 30 or 60GHz mmWave bands.

Read next: 5G vs Gigabit LTE: the differences explained

In addition, CBRS is versatile enough that a range of business cases will be supported, from in-building wireless, to smart cities, rural networks (where previous bandwidth was limited), and more.

The CBRS space is very hot, to say the least. The big carriers have been visiting FCC HQ earlier in April to appeal for bigger licensed areas to reduce costs. The industry is actively trying to sway participants to reach a compromise that suits both PAL and GAA operators, and we expect news on that front within the next weeks and months.

Thank you for being part of our community. Read our Comment Policy before posting.