Affiliate links on Android Authority may earn us a commission. Learn more.

Nintendo's DeNA deal is a bad sign for the Japanese video game industry

Published onMarch 18, 2015

At the risk of sounding overly dramatic here, I was absolutely devastated at the news from yesterday that saw Nintendo finally take the plunge into smartphone apps… with none other than IAP king, DeNA. In the decade I’ve spent in Japan, there has been a lot of surprises, but perhaps none as large as this. Let’s explore just what the Nintendo partnership means and what may-or-may-not occur.

On DeNA

DeNA has been around for a long time, though in days of old it was largely known by the “Mobage” free game portal and auction sites it had for Japanese feature phones. The enterprise gradually expanded, and when the smartphone revolution began, DeNA, along with its rival GREE, were quick to make use of IAP systems to collect cash. The company currently has a market cap of around 210,000 million yen (about $1.73 billion) and a whopping sixty (60) different apps on the Japanese Google Play Store, all of which are free to download.

Unfortunately, the success would be called into question. The company’s enormous income was in no small part driven from the obscene amount of money its users were spending on “gacha” items. The term refers to a lottery-type system wherein you pay money to get a random item, then after collecting enough random items, you can get a new, even better item. Japanese consumers in particular are known for their tendency to want to “collect ’em all” be it trading cards, Pokemon, or even virtual items. With some customers spending what might be over $10,000 in a single month, the Japanese government sought to crack down on the practice under the guise of consumer protection advocacy. As could be imagined, the stock price for DeNA and its cohorts fell an insane $3.8 billion in market cap when the Tokyo Stock Exchange opened the following Monday.

There is nothing intrinsically wrong with DeNA any more so than there is with its peers. Even the gacha system isn’t unique to Japan. If anything these businesses should be applauded for their almost subliminal way of getting users to spend money on products that are, in theory, totally free. That they can make so much money as a result is simply a testament to ingenuity behind their deceptively simple applications. As for if this kind of business partner is right for Nintendo on the other hand, is another matter entirely.

On Nintendo

By now most people are familiar with Nintendo, and chances are their memories are (a) from childhood, (b) extremely happy, and (c) filled with love for the company’s venerable IP catalog. Mario and Luigi. Link and Zelda. Pikachu and Ash. Fox and Peppy. Donkey Kong and Diddy. Even the more niche franchises such Pikmin are held in high esteem in the gaming community. As Nintendo has gradually faltered over the years, in part due to arrogance and in part due to its failure to adapt to modern times, even its most staunch critics have exchanged harsh words, out of love for what once was, and out of concern for what might never be. No one wants to see Nintendo die, but at the same time, they don’t want to have to buy Nintendo’s hardware to play the products either.

Nintendo, in turn, has been rather adamant about its plans. Despite the fact that its current president has promised to step down several times in the past due to his inability to produce results (i.e. profit), he is still there, and still as questionably competent as-ever. Many saw his decision last year to forgo the mobile gaming community as the epitome of his foolishness, especially given how much money the company stood to make from the revenue. Of course this was before the shameless Nintendo Amiibo toys were released.

To this day, people still ask for their favorite game franchises to appear on their smartphone’s mobile store. Ports or not, they want to game on the go and not be tethered to some antiquated notion of a “handheld console” as Nintendo would seek them to be. Indeed, it’s a fair argument: if the PMP genre has died (don’t tell Sony) in light of integrated media players in our phones, why, then, do we need portable gaming consoles?

What’s all the fuss about?

While DeNA might not be such a household name outside of Japan (or Asia), chances are you’ve heard of similar ventures such as King, which seemingly took the role of last decade’s Zynga. King in particular has been the subject of much criticism whether it’s the bizarre inclination it had to trademark the word “Candy” or the seemingly endless number of editorials that have been written about the manner in which its Candy Crush title becomes exceedingly addictive and compels users to spend on micro-transactions. The fact that it’s all tied into Facebook means that even if you aren’t playing, someone you know probably is, and then you need to log in to help them out.

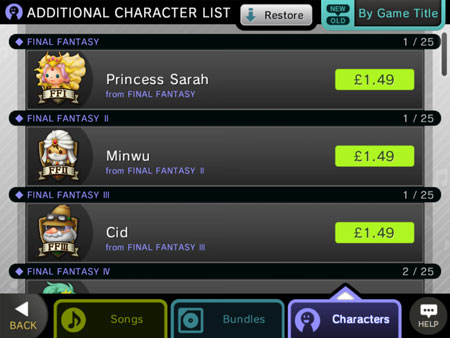

Perhaps one of the best examples of what “could go wrong” with this partnership is to look at Square Enix and the manner in which it has whored out Final Fantasy and Dragon Quest in recent years. In particular, consider the Theatrhythm series. The games are little more than simplistic rhythm outings that draw entirely on the use of music tracks from the source’s history. The games come with a set number of tracks, but of course more can be downloaded. For a price, of course.

While Nintendo gave this a try with New Super Mario Bros. 2, at least there was a substantial game to offer up, and said IAP content wasn’t the main part of the product. Would you really want a mini-game themed Mario for mobile that requires you to shell out $1 every time you want to unlock something? I’d argue people don’t want to spend money period, but the fact that it’s Mario means they (or their kids) are more likely to do it.

Oops, Nintendo did it again…

Nintendo has, arguably, never been a truly “innocent” company when it comes to its IP. Going back to the 80’s, the very games it produced required quarters to play at arcades, and thus ironically was a quasi-IAP system before IAP ever existed. As the consoles progressed, the exploitation of the Mario Bros. in particular could be seen in television shows, books, clothing, etc. By the time the 20th anniversary of the Famicom hit, Nintendo was seemingly more interested in generating revenue from reliving the past than it was producing anything substantive in the present.

This focus on the past has resulted in another of the company’s major criticisms, that it relies too much on porting games ad nauseam. This habit is – in theory – no different than say, Lucasfilm re-releasing Star Wars in theaters for the um-teenth time, or even rival game companies putting their old software library on modern platforms. Still, one need only ask a Chrono Trigger fan just what they think of the IP owner’s contention to do nothing with the rights and let’s just say, things can get ugly.

What the real problem is

Nintendo’s partnership with DeNA is of particular concern because of the very nature of the content itself. Nintendo has already announced the new platform won’t be a place for porting existing titles. The only way to play them is, and will continue to be, on Nintendo hardware. Instead, the strategic alliance is going to focus on making new software with Nintendo’s IP. Two divergent paths spring up:

Optimistically speaking, the future products will be along the lines of such recent ventures as Hyrule Warriors. They will have a large budget and be overseen by key Nintendo staff members to ensure quality and commitment to the core values of the company’s high standards for entertainment. There might be some titles of, shall we say, a more questionable nature, however thinking back to some of Nintendo’s less-than-shining moments, everyone makes mistakes. This scenario will require a lot of time, effort, and money to ensure that top quality games are made.

Realistically speaking, it’s more likely that the future products will be a shameless IAP onslaught that degrade the core of Nintendo’s once-proud franchises. The fact that DeNA was chosen almost suggests this will occur (though the extent to which remains to be seen), as it has such a strong and clear history of free to play titles. What we are seeing now is premeditation; for this to work, Nintendo must be absolved of the repercussions. They have the perfect alibi: DeNA will be blamed for the exploitation of Mario and the shameless way in which he is being prostituted, thus leaving Nintendo off the hook. DeNA, in turn, won’t be held in contempt of whoring out Mario because of a “that’s what we do, what do you expect” type approach. Think about it. It’s the perfect crime. It’s brilliant.

Wrap up

Yes, it’s true. Nintendo isn’t some saintly entity, and it’s not a non-profit organization. Like any company, it functions as a product of consumer spending, and as times change (and it doesn’t) the cash becomes harder to come by. That Nintendo needed to start developing software for smartphones and tablets isn’t, and has never been, the problem. There is an endless amount of financial reservoirs waiting to be tapped and it would be foolish not to.

Still, Nintendo has held to the idea that it’s a game company, that its core focus is on its hardware and support of it, and inadvertently, that it’s more “wholesome” than its quick-to-make-a-buck peers that have all but sold out to the glory of IAP, by watering down their IP to untold extents. Today’s announcement is both profound and prolific, for it is arguably the day that the Japanese videogame industry has truly, truly died. When the last bastion of gaming wholesomeness and child-friendly focus climbs into bed with a soulless, customer exploitative entity that even many of its addicted users wish they could drop, then things can only go downhill.

To end with an odd parallel, consider Lucasfilm and Disney. In some regards, this situation is a direct parallel: Nintendo is the former and DeNA is the latter. Despite the Star Wars company’s insatiable marketing onslaught, the franchise itself always felt a bit “protected” given that the core was but six movies. No more, no less. Notice, then, how Disney wasted no time at all in its decision to announce an entire series of Star Wars side-stories in addition to the main installments. Because it’s not enough that three new movies will release. Therein lies the core problem with the modern era of marketing: nothing is too much, and yet everything is not enough.