Affiliate links on Android Authority may earn us a commission. Learn more.

The case for regulating our smartphone use

December 6, 2017

Your smartphone is your connection to family, friends, and the world. It’s your camera, your music, your social networks, your videos, your games, your apps. It’s your essential device.

So, far be it from us to dictate how your smartphone should be used.

But for just a second consider it.

Usage

A typical smartphone user checks their phone 47 times a day, with those aged 18-24 checking 86 times a day, according to a Deloitte survey. 89 percent check their phones within an hour of waking up. They touch, tap, or swipe their device 2,617 times per day. That’s a million touches per year, just for an average user – it’s as much as double that for heavy users, a group dominated by 18-24 year-olds.

Android users across the globe used apps on their phones for just short of 325 billion hours in just three months of 2017, or 37 million years. That’s up 40 percent from the same period in 2016 and doesn’t take anyone on iOS into account.

Android users spent 325 billion hours on their apps in just three months.

By comparison, US TV owners watch around 98 billion hours or 11.2 million years of TV (including cable and streaming services such as Netflix) each quarter, mostly live broadcasts.

In late 2016, the entire Xbox userbase, across 15 years of gaming, had just cracked 100 billion gameplay hours. Android users are more than tripling that figure in just three months.

While gaming is growing and TV watching has stagnated, smartphone usage is still gaining at enormous rates. It’s a monster.

But are we enjoying our devices and apps that much, or are we just hooked?

The tech elite limit phone usage

Ex-Facebook president Sean Parker told an audience in November, when candidly discussing the giant social media network which he helped grow, “God only knows what it’s doing to our children’s brains.”

Parker exposed Facebook’s early ethos and approach to acquiring the billions that use the service: “The thought process that went into building these applications, Facebook being the first of them, was all about: ‘How do we consume as much of your time and conscious attention as possible?'”

Facebook insiders are voicing concerns on the ambitions of the company.

Other former Facebook insiders, like co-creator of the Like button (then called the Awesome button), Justin Rosenstein, have spoken out on how the company’s ambitions trump the best interests of users.

“If we only care about profit maximization, we will go rapidly into dystopia,” said Rosenstein in a Guardian interview.

Rosenstein also admitted to restricting or banning himself from platforms like Snapchat and Facebook.

Silicon Valley start-up Dopamine Labs co-founder Ramsay Brown freely admitted in a November interview with 60 Minutes that his company is designing apps and games for addiction.

“We’re really living in this new era that we’re not just designing software anymore, we’re designing minds,” said Brown.

The unhealthy addiction, also known as the attention economy, is clearly being avoided by the elite.

“Yes, the planet got destroyed. But for a beautiful moment in time we created a lot of value for shareholders.” The New Yorker pic.twitter.com/5QFzsdrWtg— Christopher Prentiss Michel (@chrismichel) June 2, 2017

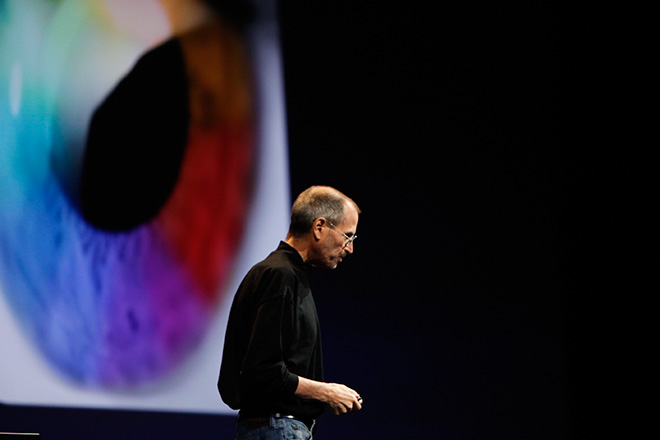

Both Bill Gates and Steve Jobs – the men who created the hardware and software that lead us to this point – professed to limiting the hours their children spent with devices. Jobs admitted in a 2011 New York Times interview his family limited their children’s technology.

Gates, with wife Melinda, set limits on screen time, and didn’t allow his three children to get a smartphone until they were 14.

The tech elite who school their children in Silicon Valley, send their children to speciality low-tech schools, such as Waldorf or Steiner schools, or Brightworks School, where children learn creativity, not coding. iPhones, iPads and laptops are banned.

If engineers, creators, and leaders working to limit screen time and social network access isn’t enough to give you pause, what about the studies which look at what happens to us when hooked to our devices.

How smartphones affect us

We’re distracted. In a University of Texas study, cognition capacity for test students got lower if a smartphone was even nearby, even when the device was completely off. In fact, the closer a phone was to a student, the worse the result, with best results when students had their phone in a completely separate room.

Our relationships appear to be damaged by smartphone necessity. A study published in the journal Psychology of Popular Media Culture found college students that with smartphone dependency show much more relationship uncertainty. On the flip side, those who saw a perceived smartphone dependency by their partners were less satisfied in their relationship.

Our relationships are suffering at the hands of our smartphone dependency.

A well-cited study by the National Safety Council points to more than 27 percent of all car crashes in America are likely caused by cell phone use – talking, texting, or usage of a smartphone for navigation, music, and so on. (The NSC created this estimate believing cell phone-related crashes are underreported.)

San Diego State University psychologist Jean Twenge stated that rates of teen depression and suicide have ‘skyrocketed’ since 2011, citing research that found teenagers in eighth-grade, who attest to frequently using social media, increase their risk of depression by 27 percent.

Rates of teen depression and suicide have ‘skyrocketed’ since 2011

Those that regularly engage in sports, do their homework, or even go to religious services more than the average teenager, cut their risk significantly. But according to Monitoring The Future, teens are getting less sleep, driving less, dating less, playing less sport, aren’t seeing their friends outside of school, and are more likely to feel lonely.

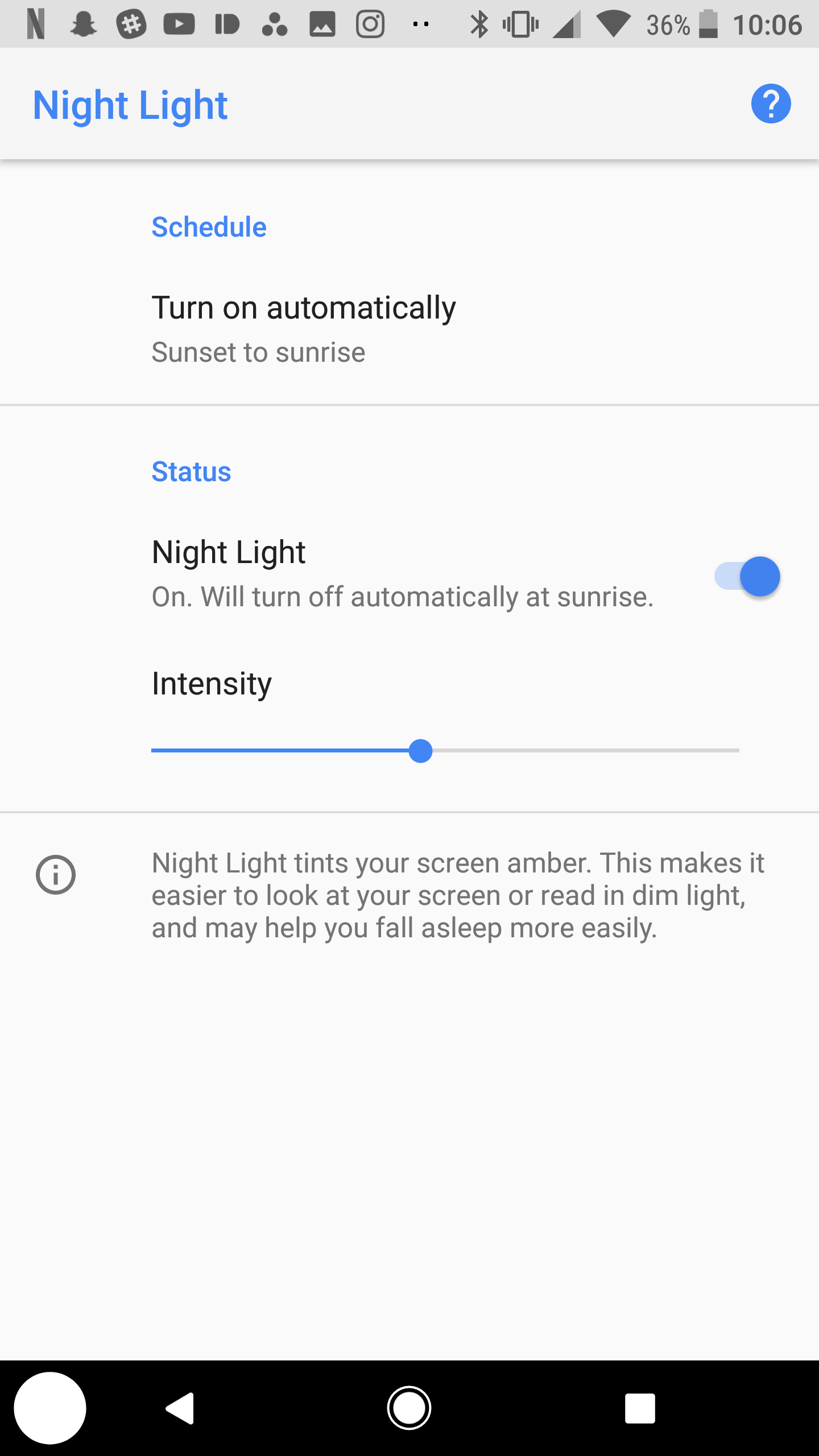

When we try to sleep, our phones may be stopping us from getting quality shut-eye. A study published in the Journal of Psychiatric Research found that use of blue light LED smartphones at night decreased sleepiness, slowed the production of melatonin, and caused users to make more errors. It was serious enough for Apple to introduce Night Shift in iOS 9.3, back in March 2016, following both the science and the emergence of apps like f.lux, and Android makers followed suit.

A huge Harvard study looked at the health of heavy smartphone users, following 25,000 US teens, and found 20 percent spent more than five hours a day in front of screens. This set of young adults were 43 percent more likely to be obese, and had double the chance of being both sleep deprived and not getting enough exercise, when compared with those that spent less time on their phones.

It gets worse. We’re more distracted, sleeping less, and feeling empty, lonely, or worse, suicidal. Teen suicides now outnumber homicides, and that’s not because homicides are falling. Twenge pointed out more device usage is positively correlated with suicide risk factors. Teenagers who spent at least three hours a day on a device are 35 percent more likely to have searched Google for how to commit suicide.

Not only are we distracted both at work and behind the wheel, we're tired, lonely - and contemplating suicide.

Girls are catching up to boys quickly in this. Three times as many 12-to-14-year-old girls killed themselves in 2015 as in 2007. Twenge said this is likely down to cyberbullying, which is more prevalent in girls, who work to “undermine a victim’s social status or relationships” with social media, providing a platform for “ostracizing and excluding other girls around the clock.”Boys the same age doubled their suicide rate, overall higher than girls, over the same period.

Researchers are careful to point out that in most cases, smartphones are exacerbating existing behaviours, rather than being the root cause. Links between smartphone usage and negative behaviors or outcomes are often significant, but could be coincidental, or come from other missed factors. Many might say that similar findings were made about TVs, PCs, and the internet. But smartphones are a more personal technology, so effects are powerful.

Suspicious patterns are clear, and growing.

Fighting back: Using apps to counter apps

Even knowing these facts to be partly true, the idea of perhaps limiting smartphone use would likely be met by most with an answer involving some variety of “from my cold dead hands.”

When you know something is bad for you and continue to do it anyway, you’re very much in the realm of addiction.

We’re beginning to be more conscious of our behavior: in two recent studies, including the 2017 Global Mobile Consumer Survey, a 47 percent of adult Americans said they were ‘making a conscious effort to reduce or limit’ the duration or frequency of smartphone use.

47 percent of adult Americans said they are ‘making a conscious effort to reduce or limit’ the duration or frequency of smartphone use

The American Psychological Society offers a range of digital guidelines, especially for those with children, around forming healthy habits to not overreact, discussing decision making, protecting bedtimes, and fostering real-life friendships.

For adults, some are finding success with a somewhat counter-intuitive approach in using apps to limit usage.

Checky (free for Android and iOS) gathers data about your phone use, showing you how many times you unlock your phone in a day and logging this behavior over time. Charting your progress might just be personal enough to cause you to rethink.

AppDetox allows you to set rules for individual apps, such as limiting time in Facebook to 30 minutes a day, letting you launch it six times a day only, or only allowing you to access an app at certain times.

Onward, Freedom, and Flipd are all similar, with premium options for cross-platform or longer lock times and data.

Forest, an app that harnesses what hooks us into free-to-play games, gamifies the process of limiting distractions. By staying in the Forest app, a planted seed turns into a tree as a mindful and peaceful reminder to keep you on task.

What now?

Technology changes so rapidly that accurately predicting where one trend will end and another will start is impossible. At the moment, the quality and performance of our smartphones continues to improve, and augmented reality remains on the horizon, albeit without significant technical breakthroughs.

For now, we’re locked into a smartphone world. Every statistical measure shows we’re using our devices more and more. The tomes of data from researchers will sharpen the focus of how that is affecting us, but the early signs aren’t good.

It’s not hard to see the warning signs. We remain in control, but we’re not pulling back. We’re susceptible. We’re exploitable. We’re addicts. Companies (and their neuroscientists) are working to make their apps as successful as they can to grow, at a cost to us. But who’s got the time to fight back when we’re so busy with our phones?

It’s not hard to see the warning signs. We remain in control, but we’re not pulling back. We’re susceptible. We’re exploitable. We’re addicts.

It’s unlikely that regulation from lawmakers will step in at any point in the future, for many reasons from practicality to the lack of dramatic, vote-gaining necessity.

That means it’s down to the very tech corporations that have us hooked, or maybe a new disruptor, but they aren’t looking very likely these days.

The best answer for now is just to try monitoring your usage, and see how you feel if you try an app or a physical constraint to set limits or boundaries. Like any addiction, weaning yourself off your phone is not going to be easy, so if you’re interested in limiting your usage, take it slow, set achievable goals and be honest with yourself.