Affiliate links on Android Authority may earn us a commission. Learn more.

Supreme Court says police must obtain warrant to get phone location data

Published onJune 22, 2018

- In a 5-4 ruling, the Supreme Court decided that law enforcement generally needs a warrant to collect and access phone location data.

- The decision reversed and remanded the Sixth Circuit court’s decision.

- At the heart of the case is whether phone location data falls under Fourth Amendment protections against unreasonable searches and seizures.

In a win for privacy advocates and a blow to law enforcement officials, the Supreme Court ruled that the police generally need a court-approved warrant to gather phone location data as evidence for trials.

The 5-4 ruling fell in favor of Timothy Carpenter, who was convicted in a string of armed robberies of Radio Shack and T-Mobile stores in Ohio and Michigan. In addition to witnesses, prosecutors also relied on months of data obtained from Carpenter’s phone provider.

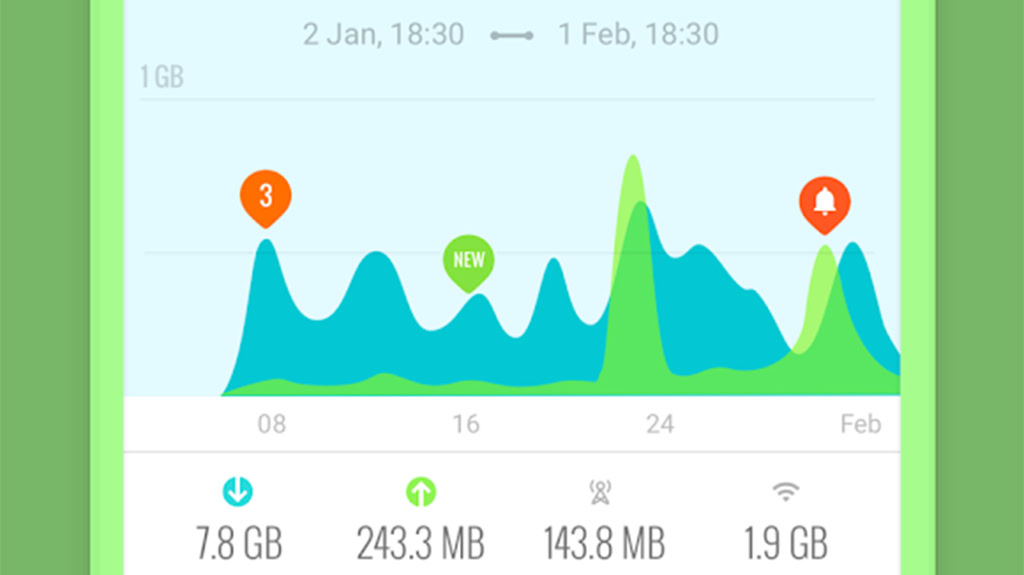

According to the data, Carpenter’s phone was close to where the robberies took place. However, his lawyers said his phone provider turned over 127 days of records, which placed the phone at 12,898 locations. The data disclosed whether Carpenter attended his regular Sunday church visits or slept at home on certain nights.

Even though Carpenter was sentenced to 116 years in prison, the question remained as to whether prosecutors violated the Fourth Amendment. Law enforcement collected Carpenter’s digital footprints without a warrant, which would kick in the Fourth Amendment’s protections against unreasonable searches and seizures.

A Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals judge ruled that phone location data does not fall under the Fourth Amendment. Therefore, law enforcement officials did not require a warrant to obtain Carpenter’s records.

The Supreme Court’s decision, however, reversed and remanded the Sixth Circuit court’s decision. In the Supreme Court’s ruling, Chief Justice John Roberts wrote that Carpenter’s phone records were considered a Fourth Amendment search:

“The Government’s position fails to contend with the seismic shifts in digital technology that made possible the tracking of not only Carpenter’s location but also everyone else’s, not for a short period but for years and years.”

Roberts also wrote law enforcement infringed Carpenter’s Fourth Amendment protections and expectation of privacy when they were granted access to Carpenter’s historical GPS data. Historical GPS data, wrote Roberts, poses an “even greater privacy risk” than real-time GPS data.

In a statement sent to Android Authority, the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF) said it was “extremely gratified” with the Supreme Court’s ruling. The EFF also said the Court “sent a strong message by recognizing that cell phone tracking has the capability to lay private lives bare to government inspection.”

In a separate statement, the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) said the Supreme Court’s decision “rightly recognizes the need to protect the highly sensitive location data from our cell phones, but it also provides a path forward for safeguarding other sensitive digital information in future cases — from our emails, smart home appliances, and technology that is yet to be invented.”

What happens now?

Carpenter v. United States is the first case that the Supreme Court ever ruled on in regards to phone location data. As such, this could set a precedent for similar cases in the future and could lead to existing laws seeing some changes.

For example, the Stored Communications Act does not require prosecutors to have probable cause to obtain tracking data. Prosecutors need only demonstrate that there were “specific and articulable facts showing that there are reasonable grounds to believe” that the sought-after data is “relevant and material to an ongoing criminal investigation.”

Also consider that all four major U.S. carriers will no longer sell real-time location information to data brokers that then sold that data to other companies. Whether lawmakers will scrutinize such practices is anyone’s guess, though U.S. Senator Ron Wyden of Oregon did not take too kindly to the news.