Affiliate links on Android Authority may earn us a commission. Learn more.

No, your phone is not always listening to you

Published onJuly 18, 2018

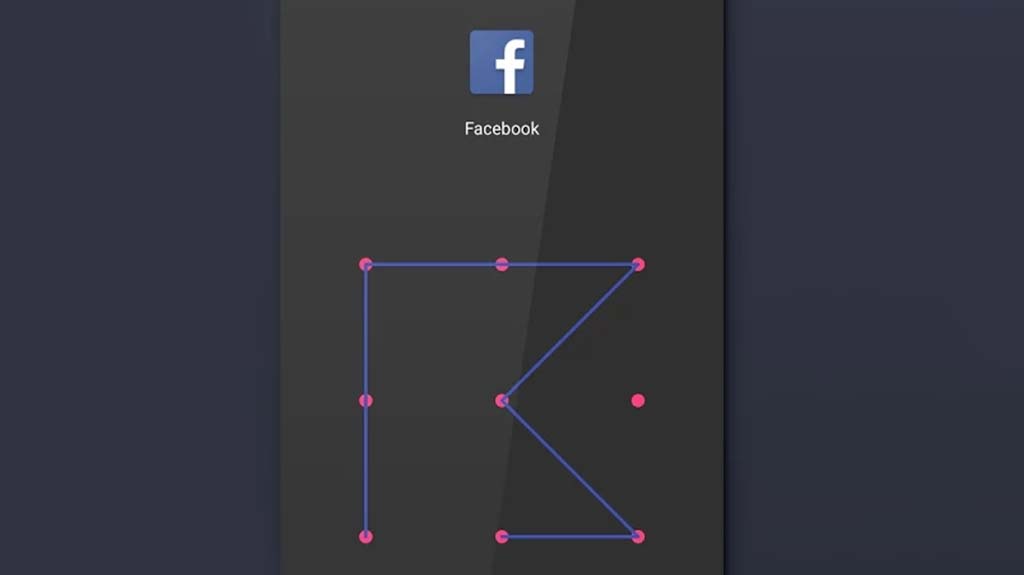

One evening you’re talking to a friend or partner about some holiday you want to take, a major purchase you’re mulling over, or the latest movie you want to see. Your smartphone is probably on the coffee table or tucked away in your pocket. The next day, your Facebook feed is full of ads related to last night’s topic. You’ve might have experienced this yourself — it’s an increasingly common experience among tech users. If you believe anecdotal ramblings, there’s only one culprit.

It must be my phone — the damn thing must be listening to me! After all, it has a microphone, and it was the only other thing nearby. But are these just paranoid delusions or a glimpse into something even more sinister?

The evidence says …

No, your phone is not listening to you.

Various research attempts have failed to find evidence of smartphones secretly listening and transmitting voice data. Observing the data that smartphone applications and the OS record and send out is a reasonably trivial affair for security researchers. Even if we can’t read encrypted data, it’s at least possible to see if data is being sent and to where.

Despite the endless conspiracy theories, no one yet found compelling evidence that Facebook, Google, or any other major tech company has been recording user voice data without their consent. Amazon and Google are reasonably upfront about the fact that data recorded by their assistants is saved online, but customers can view and delete this data. Google’s developer content policy also rules against apps recording user details without consent. Facebook also previously clarified its position on voice recording too, although it might be naive to just take its word for it.

These theories are based on anecdotes, confirmation bias, and specious reasoning, rather than rigorous testing and evidence.

The legal situation regarding wiretapping, ownership of recordings, and biometric information of voice and image data is a grey area right now, but any collection of this data without consent would inevitably result in very expensive class-action lawsuits. Google has already been embroiled in suits regarding web browser tracking, as has Facebook for call logging — even though the personal information collected was minimal. Secretly collected voice data would almost certainly see the payouts reach new heights and lead to major interventions from national legislators.

The subsequent PR scandal, should such a breach immerge, would arguably be even worse for any of the companies involved. The Cambridge Audio Analytica scandal gave us just a glimpse at the PR nightmare that would engulf a company caught secretly recording and sharing sensitive user information.

This doesn’t rule out the possibility it is happening, but it’s an awfully large risk to take just to scrape a little bit more user data. We already give so much of it away for free anyway.

Voice recognition is complex and expensive

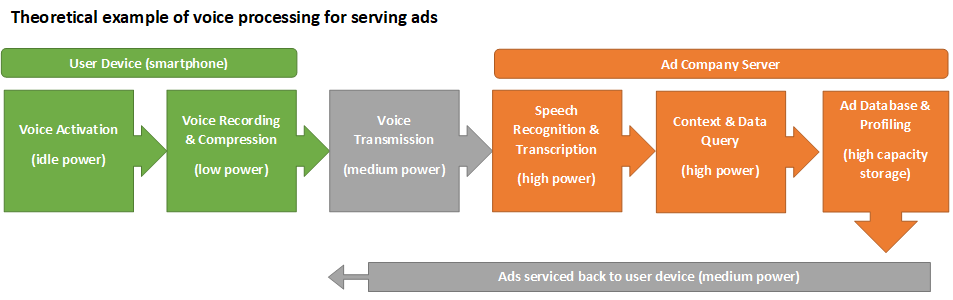

If you’re not yet convinced, step back and think about what would actually be involved in listening to not just you, but to every smartphone user in the world, all just to detect keywords of interest. There are two options to do this, ship recorded data off to big machine learning server farms or process the voice data on your phone locally.

The latter isn’t very likely, because machine learning on this scale on a phone would be prohibitively taxing on the battery as well as on the storage costs to save the neural network and regularly updated keyword databases. Despite what some believe, keyword detection like “Hey Google” is only used to wake up a device from a low power state to perform more powerful listening, it’s not helpful for data tracking. Increasing the number of keywords to thousands or more (which you would need to cover the range of possible ad topics) requires more processing power and therefore defeats the purpose. Your battery would drain very noticeably if your phone was always listening for thousands of possible words.

Furthermore, keyword detection is useless at providing context. How often do you think people realistically say “I want to buy new shoes” to trigger a key phrase? People will talk about shoes in a variety of contexts, so simply triggering on the words “buy” or “shoes” isn’t helpful. Perhaps you’re just complimenting a friend on their latest pair. A high-quality ad-hunting speech-to-text system would have to sift through all of your conversations to pick out keywords and sentences, and then put them into context about products, people, places, and various other categories for advertisers to use.

But contextualization is very data heavy compared to keywords. Some combination of voice detection and audio compression to trim down the amount of data sent for processing is the most realistic method to achieve good results.

Let’s assume Google’s very efficient iLBC 15kbps VOIP Codec sends voice data to servers (compressing audio down with a codec is also battery taxing). ILBC gives us a tiny 112KB of data per minute, but a more noticeable 6.7MB per hour, 162MB per day, and huge 59GB of data a year per user for 24/7 monitoring. You’d certainly need a big data plan to avoid being capped. Even trimming that down from 24-hour monitoring to just one hour of condensed data requires 2.5GB per user a year — about 6 Exabytes for the 2.5 billion smartphone users out there. That’s no small amount of data to conceal, let alone process.

For every snippet of useful ad data, there would be hours of idle chatter to contextualize, even with keyword detection. We'd be talking Exabytes of voice processing a year.

Perhaps more prohibitive would be the sheer cost of processing this much voice data. Speech-to-text services aren’t cheap to deploy, even if you’re Google. The tech giant sells its Speech Recognition system to third parties for $0.006 per 15 seconds of audio. To record just you 24/7, that would cost $34.56 a day or $12,614 per year. Even with just 1 hour of audio data a day that only brings the total down to $525 a year. Scaled up to the 2.5 billion smartphone users, that’s $1.31 trillion just for voice processing. That’s not counting the data storage, processing the transcripts, database integration, networking, and other associated expenses, nor doubling up on devices like smart home speakers, TVs, and laptops.

Even if we assume Google could do all of this in-house at a fifth the price (a generous estimate), that’s $106 per consumer for a total of $264 billion per year to record every smartphone for just 1 hour per day.

Global media ad spending for 2018 is expected to hit $628.63 billion, while digital ads for phones and the like are estimated to be worth around $266 billion. Based on our rough estimate, just processing everyone’s voice would easily consume the entire world’s digital ad budget, leaving nothing left to purchase any ad space. Clearly not a very profitable venture.

Processing everyone's voice for just 1 hour per day would consume the entire 2018 digital ad budget.

Finally, consider the technical and financial absurdities above and remember that this applies for just one company. However, Google, Facebook, Amazon, IBM, Microsoft, and countless others are interested in your data, and if one of them is recording you why wouldn’t they all be at it at once? The costs would easily be multiples higher than we’ve estimated here, it’s simply not economical.

There’s a simpler explanation

So if it’s not true, why do stories and our own experiences with ads feel like we’re being listened to? It all seems far too accurate to be a coincidence, right?

The law of large numbers is likely the culprit. Even with sophisticated targeted advertising, we skip past hundreds of ads each day that don’t seem relevant to us. It only takes one eerily accurate ad experience to convince us that someone must have cheated and gleaned some insider information. It’s the same phenomenon that convinces people vague physic readings and horoscopes are related to their lives — one accurate coincidence is enough to overwrite the countless misses.

Although it seems improbable that an ad for a new watch would appear just minutes after yours stopped ticking, you might have been skimming over similar ads for weeks without noticing. Furthermore, very subtle things we give away can quickly flag a very accurate ad. If you’re of child-bearing age, don’t be surprised if you start seeing maternity product ads after logging into the free Wi-Fi at Baby Gap.

Big data is even scarier

Ultimately, the “classic” methods of data acquisition and consumer profiling are much much cheaper than processing audio hoping to eavesdrop on a product we might want. Big data collection lets companies learn an awful lot about us by drawing data from a variety of different sources.

Targeted advertising sorts us into buckets or categories based on demographics, interests, and relationships, which companies pay to pitch advertisements to. Even regularly visited locations, YouTube video history, previous purchases, and website cookies, contribute to a refined profile about your tastes, personality, and spending habits.

Joining the dots between our various social and shopping accounts, and even multiple devices, reveals an even bigger picture, not just about us but about those we interact with. Combined with more invasive forms of tracking, such as Wi-Fi hotspot locations, Bluetooth proximity, and email scanning, and it’s easy to see how a network of our behaviors, preferences, and even the more intimate details of our lives begins to appear.

You constantly skip past ads that one day may suddenly become relevant.

This huge web of data can result in more mundane ads, like ones for games to play on your new Nintendo Switch, or creepily insightful suggestions, for things like engagement rings and maternity wear or even the new Italian restaurant you’ve been meaning to try downtown. That trip you haven’t told anyone you’re taking to East Asia isn’t such a secret if you’ve left a trail of crumbs made of Maps searches, sandal purchases, Facebook likes, Instagram follows, and your latest online reading habits. Even if you haven’t specifically typed your destination into Google, big data can join the dots to present those eerily accurate recommendations.

Big data can be so accurate as to anticipate our wants before we even realize them. Sadly, we’re just not as unique or unpredictable as we might like to think.

Wrap up

In summary, no your phone isn’t listening to you 24/7 — it simply isn’t feasible technologically or economically. Even though microphones can record with no noticeable battery drain, the raw computing power and expense of processing voice data would be extraordinary. Voice analysis on this scale just isn’t realistic at a price point that makes sense to advertisers, especially when other types of data collection are much more cost effective. Plus, secret recording is a PR disaster just waiting to happen.

This myth remains popular only because the alternative is harder to explain and comprehend for a lot of people. Targeted advertising still misses more than it hits. For every anecdote about eerily accurate ads, there’s another one for a terribly inappropriate product placement or consumers who see Amazon ads for something they bought last week.

Still, data tracking is very real and already highly invasive in many respects. We should all be increasingly concerned about our privacy, especially in light of data leaks and shady sharing deals. One thing we don’t have to worry about is our phones listening to us 24/7 — at least not yet.